As with any industry you care to look at, the technology industry is awash with copycats. A copycat, of course, is someone or something that deliberately mimics a successful person or product, hoping to obtain some portion of that success.

There’s an entire spectrum of terms available besides ‘copied’, ranging from “inspired by” to “plagiarised”, and it’s not necessarily a bad thing to be influenced by the work of others. The key is to ensure that you’re consciously agreeing with a design, rather than just aping (mimicking unthinkingly – a definition which no doubt does our hairy cousins a grave disservice). Sadly, much of the technology sector simply apes.

The usual suspects

One of the pre-eminent copycats of the moment is surely Samsung, whose imitation of Apple’s iOS hardware and software is not only the subject of multiple legal cases, but is also obvious upon even the most casual inspection. Here’s the Apple iPhone 4 (2010), and the Samsung Galaxy SII (2011):

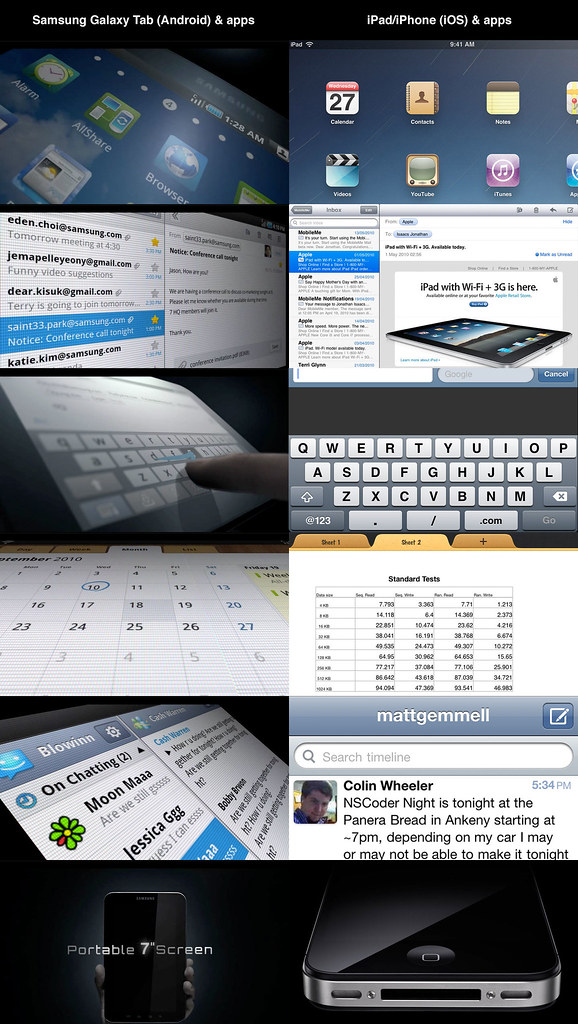

And let’s not forget the software. Here’s the Galaxy Tab Android tablet’s UI, compared with iOS on an iPad. In all cases, the iOS examples existed and were publicly released before the Galaxy Tab equivalents.

So far, so depressing. There’s nothing inherently right or appropriate about specific colour-schemes, gradients, control layouts, interface metaphors, typefaces or hardware aesthetics – they’re just design choices, backed (hopefully) by user experience testing and aesthetic sensibility. So, to produce such stunningly similar products and user experiences is the result of only two possible situations:

- Astronomically unlikely random chance (with the unlikelihood being multiplied by the number of similarities).

- Copying.

The visual evidence, common sense, and even mathematics itself says that option 2 is far, far more likely. It’s a shame, because Samsung no doubt has many talented designers, whose work briefs must be utterly soul-destroying: “Make something that’s as close to this other person’s work as possible.”

HP is probably the next-best-known culprit, with their latest example appearing very recently: the hilariously-named HP Envy laptop (2011), which mimics the design of Apple’s MacBook Pro (2008 onwards).

Why knock-offs exist

There are, of course, legitimate commercial reasons for the existence of copycat products, even if it’s difficult to justify the act of copying on a creative or moral basis. Here are a few common ones:

-

Customers require a different underlying product for technical reasons (either genuinely, or just by their own perception), but prefer the aesthetic of a competing product. This is one possible motivation for PC copies of Mac hardware, even though any modern Mac will quite happily run Windows natively.

-

Customers cannot afford the original, but for social or psychological reasons nevertheless still want a product which looks similarly aspirational and expensive. This is the other primary case for cheaper PC copies of Mac hardware.

-

The original product has become an archetype of its class, causing other products to be defined in terms of it. This is very much the iPhone and iPad example, but also applies to things like interaction methods and peripherals. For example, the Nintendo Wii motion controller (2006) was followed by the Sony PlayStation Move motion controller for PS3 (2009).

-

Customers already own the original product, and want more of the same. This tends to apply to cheap, consumable media rather than products per se. Specific examples are readily found:

- The Twilight movie (2008) was followed by The Vampire Diaries TV show (2009) (Uli on Twitter has said that the source material of the latter actually predates that of the former – I include this note to bow to his superior knowledge of teenage girls’ fiction, but the point is the same).

- The Da Vinci Code novel (2003) was followed by an ever-growing army of imitations, including The Atlantis Code (2009), The Moses Stone (2009), The Lucifer Code (2010), The Noah’s Ark Quest (2010), The Messiah Secret (2010), The Temple Mount Code (2011), The Midas Code (2011) and dozens upon dozens more.

- The X-Men movie (2000) was followed by the Mutant X TV show (2001).

- The Nintendogs game for DS (2005) was followed by the Dogz game for DS (2006).

- Countless further examples exist in all genres of products, media and services, with new ones being created every day.

In every one of these cases, it’s possible to argue – almost always successfully – that the “original” is itself a copy of an earlier product. Or, for cross-media products like movies of books, that the original order might be reversed. That may all be true, and indeed only enhances the point.

Suffice to say, copying is endemic in design. But why is that the case? I think it’s due to a misunderstanding of both what design actually entails, and also why products become successful.

The innovation problem

When designing something, ideas aren’t the problem. Indeed, even crazy, blue-sky ideas are often in plentiful supply. What kills you is reality – the actual implementation.

Your beautiful hand-waving idea is suddenly crushed by consequences, constraints and the hangman’s noose of its own gross oversimplification of the problem. That’s why a Photoshop mockup is no substitute for even a pencil-and-paper multi-screen prototype, and it’s also why fanciful “where technology will be in ten years” videos are usually little more than a stored-up source of future amusement.

The issue is that real design jobs aren’t about creating something absolutely new – instead, they’re about innovation. The etymology of the word ‘innovation’ means something like “renewing”, or changing an existing thing by adding something new or doing something differently. Not a clean-cut, start-from-scratch scenario – that’s not what innovation is, and that’s why it’s hard.

When you’re making a new phone, you’re still making a phone. There are hundreds of constraints already present. Ditto for a car, or an app to help you manage your money, or a pair of running shoes. Innovation suddenly feels like an ever-narrowing alley, with little room to move.

It’s thus pretty easy to see why copying happens – because when you see a mature product that’s somehow managed to innovate (to be “new” whilst balancing all the constraints and annoyances of the existing problem), it becomes almost impossible to see how you could do it any other way. Design blindness sets in: the most successful product is the only possible design. Which, of course, is nonsense – but a very convincing, insistent, tempting sort of nonsense.

From the perspective of pure expediency (convenience regardless of morality), copying makes a hell of a lot of sense. We’ve all been tempted. Aside from potential legal vulnerability, what’s the down-side? I’ll tell you, even though it’s something you already know. Here’s the incredibly obvious truth:

Copies never, ever achieve the success of the thing they copied.

An original design that sustains a product line for years (say, the iPhone) continues to blithely out-sell not only each individual copy, but all of them put together. It’s not an uncommon situation. Think of all the iconic products and designs that endure, and remain incredibly successful, while dozens of also-ran knock-offs appear, wither and die on a monthly basis.

The reason is simple.

Copying is harder than innovating

Say you’re sitting an exam, and you can see the answer book of the person sitting next to you. You’re stuck on a question, and she just answered it – confidently, given the look on her face. It’s much easier to just copy her answer than to sit and puzzle it out yourself.

Easier, that is, until you’re caught cheating. Or until your friend tells you after the exam that he had an entirely different answer from the one you copied. Or until you actually need that knowledge on the job. The very structure of life and the universe has a way of punishing a lack of due diligence, sooner or later. That’s just as true in design as it is when sitting an exam.

Innovation isn’t creation in a vacuum – it’s making something new from something that already exists. Pre-loaded constraints, hassles and problems. You have a simple choice to make:

- Tackle the problem on a pure (and ethical) basis, trying to make something better whilst managing the constraints creatively.

- Copy someone else’s solution because it’s popular, and easier for you.

If you picked option 2, then guess what: you just made your life harder. You’ve inherited all of the constraints that already existed, and you added more. Constraints like:

- Credibility, not just for your company but more importantly for yourself as a professional. I feel terribly sorry for the designers in the HP Envy design video, skirting around the Apple-shaped elephant in the room.

- Legal liability, perhaps for intellectual property infringement.

- The need to design from the outside in (or reverse-engineer a design) rather than the more natural process of designing outwards.

- An implied requirement to distance and differentiate yourself from the very thing you copied.

And no doubt more. The worst part is that these extra constraints are irrelevant to the core problem. You’re a man on a tightrope who just chose to tie his ankles together. Metaphorically, you’re now substantially more likely to plunge to your death. In a more literal sense, your product is now riddled with compromises.

That’s why the HP Envy has a bizarre red rim around the keyboard, and (truthfully; take a look for yourself) a volume knob built into the side of the casing as a first-class ‘feature’. It’s different in that way, so it can’t just be a copy, right? Wrong. Swaying on the tightrope.

Copying not only cripples your design with needless compromises right from the start, it also makes your marketing a nightmare. The customers who are most interested in your product will be those who actually want the original thing made by someone else. No matter what you tell them, they’re seeing this message instead:

It’s like that thing you want, but it’s not!

Genius. You’ve essentially guaranteed that every buying decision comes bundled with a kernel of regret, maybe because they didn’t have enough money, or needed a floppy disk drive, or were tied into a phone carrier contract for another year and couldn’t get the handset they’d prefer. Your product can never be ideal for its target market, because you’ve deliberately defined it in terms of someone else’s. That, quite frankly, is utterly mad.

The lesson of the technology industry in the past five years is that really successful products dare to NOT copy. They’re pure, in that they’re actually designed from first principles – they’re based on the problem and the constraints, without being viewed through the lens of someone’s existing attempt. You know, the kind of thing you actually wanted to work on when you got your degree and were still unsullied by the lazy, corporate machine.

Inspired

Innovation is about making things new, rather than necessarily making new things. To do that, you naturally need to know what things are already out there. No-one is saying you should design in a vacuum, and indeed you’ll never be able to anyway. Know the market, know your competition, and certainly live and breathe in the sector you’re designing for.

Let the stuff that’s out there flow over you, and yes, let it influence you. That’s what inspiration is – it’s being affected by something in a way that helps you do another thing. But make your designs original. It’s easier, from start to finish, even if it doesn’t at first seem that way. If your boss won’t let you do that, get another boss – because life is too short, and there’s always another boss (or client), and I really hope you can’t put a price on your self-respect.

There’s nothing new under the sun, as they say – we’re all inspired and affected by other things. All of our design takes place under constraints. So, be influenced. Incorporate elements. Agree with implementations. Understand an approach. Realise the purpose and function of a design decision. Address a need. Renew something.

Be an innovator, not a copycat.

(If you’re interested in more thoughts about product design and technology, feel free to follow me on Twitter.)