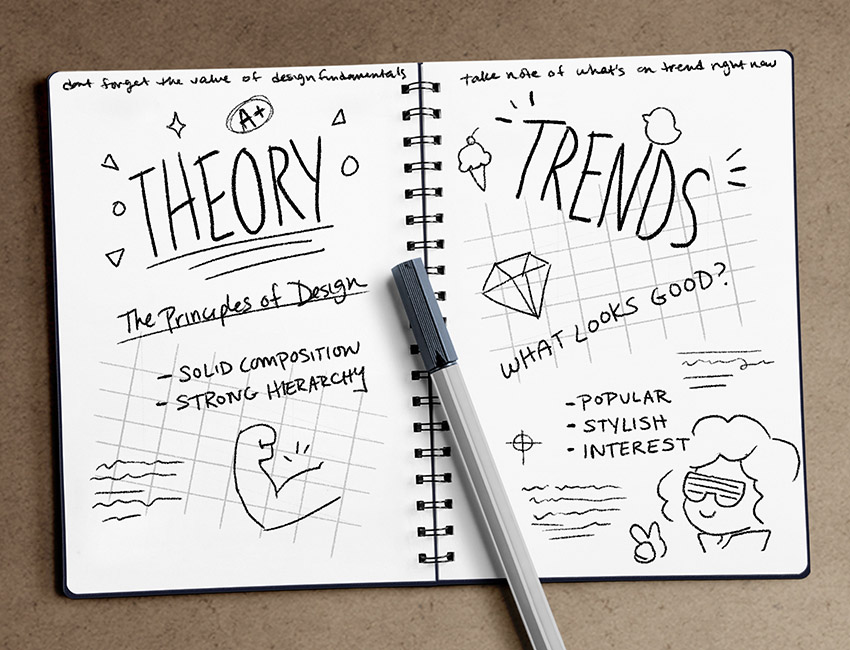

A strong design is more than application of the principles of design; it’s also in tune with aesthetics, be they trends or visual styles that make the project most visually engaging. Likewise, relying on a trendy look alone does not necessarily make for a great design. Those fundamental principles are essential.

In this article, we’ll explore the relationship between the two: design principles and design trends.

What Are Design Principles?

An Introduction

The principles of design are a set of tools that designers can use to construct a successful composition. They’re also a great source of understanding design; with these principles, we can deconstruct and understand how things work and why.

Design might seem like magic sometimes, as if lightning struck and something mystical happened. However, in most cases, it’s likely not true—a strong composition, for example, knows how to command attention in the right place, and how to employ visual supplements that complement.

Why Are They Important?

This is important because design is not necessarily “luck”. Imagine if you wanted to build a home, but you had no tools, no plans. You were just going to haphazardly start building without any idea of how or where to place things.

Now, don’t get me wrong here—this builder might make some great things, but working without a strategy is not necessarily a recipe for consistent success.

Personally, I’ve found that once you get familiar with design principles, they start to feel like clockwork—just like being familiar with software, you just know how to do certain things after a while.

Let’s take a look at a brief overview of what these principles are.

Hierarchy

Think of hierarchy like a system of visual order or importance. If everything in the composition is fighting for dominance, it might look overwhelming. Likewise, if nothing stands out as a focal point, where do we look? How do we guide the viewer’s eyes in the composition?

Note, in the below example, how the title stands out as the focal point—it’s where your eyes start. Likewise, the body copy plays a considerably more supplemental role.

Rhythm and Repetition

When things repeat, they tend to blend in with each other. Think about patterned wallpaper, for example. The repeated elements start to feel expected and ambient, as a smaller part of a larger whole.

We can also use repetition to establish a sense of harmony—like having matching footer elements cross several pages in a document, or having other visual elements that consistently repeat.

In the example below, notice how the circles don’t vary. They repeat and feel like one continuous pattern.

Variety

I often look at variety as the opposite of rhythm and repetition. This isn’t about repeating; this is about mixing things up and standing out. Variety often creates interest. For example, observe below how the big red rectangle stands out against all the smaller gray triangles.

Why?

This rectangle is larger, a different color, and a different shape—so it really commands our attention.

Contrast

A simple way to describe contrast might be “light and dark”—they’re opposites. However, contrast as a design principle is a little more complicated than that. For example, we can also use contrast to create variety or interest. We can use contrast to alter readability and/or visibility.

In the bottom example, notice the stark contrast between black and white—versus the lessened intensity of the gray samples.

Balance

Balance, as it sounds, refers to a visual sense of weight. So, for example, if the majority of the content is on the right-hand side of the composition, the balance would likely be considered asymmetrical. Compositions can also have symmetrical or radial (as in radiating outwards) balance.

However, design is often more complicated than “put everything on the right”—it’s about proximity, visual relationships, and making sure the parts of the composition are balanced in a unified way.

Proportion and Scale

When you think about proportion, you might think about the size of something—particularly about size in relationship to something else. This is how this design principle works, too. For example, the title in a composition might be much larger than the body copy. We can use scale, in this way, to experiment with these size relationships.

Proximity and ratio are sometimes grouped with these principles, as they deal with the visual relationships that parts of your composition share.

For example, notice how both the size and the spacial relationship shared by the words “Hello There” make them look like a continuous phrase. If we add space between them, as well as variation in scale, suddenly they don’t relate in the same way.

Emphasis

Emphasis is your focal point—it’s a point of interest, where you want your viewers to look. This is often achieved with variety, as we discussed earlier, but we could employ many different strategies to achieve emphasis.

For example, notice how the floral element “points” to the word “Title”—it’s driving our eyes there, via movement. The world “Title” is also quite large and dark. It commands our attention!

Movement

That said, let’s look at movement! As the name implies, it’s about guiding our viewer’s eyes through the composition. Think about your viewer’s preconceived associations. Many viewers might read top to bottom, left to right—we can play into this association, when creating a composition. However, we can also use color, value, line, and a number of elements of art to imply movement.

In the below example, note how the plant stems seem to lead the eyes to the headline. They “point” to it.

Unity

Unity is the finish line—it’s perhaps the toughest design principle to really capture, because it’s a general sense of completion. Everything is in place. Everything is working together to make a solid composition that is visually accessible and engaging.

Examples of Design Principles in Use

Let’s point out the principles of design in a real-world example. This poster design, below, was created by Joe Caroff for West Side Story (the 1961 film).

Think about where your eyes initially “go”. I would argue that the emphasis is on the title—it’s very large, and it commands our attention.

We see interesting contrast here—the figures are the same, but one set is black and the other is white. This visually communicates in relationship to the story itself.

The balance is asymmetrical, which leads to a rather informal aesthetic. There’s interesting movement here, implied by the ladder-like shapes. Notice scale in the typography; see the hierarchy? The text gets smaller, and it creates a system of importance here (i.e. the title is more “important” than some of the supplemental credits, in terms of visibility).

See what other principles of design you can spot here!

What Is a Design Trend?

The Art of Looking Great

But design is more than just principles—it’s about looking great too, and “what looks great” isn’t always the same. Things like culture, time period, and industry can really affect “what looks good”—or what’s popular.

Remember how popular flannel was in the 90s? Well, you might or might not, depending on factors like where you lived and how old you were—and that’s the point.

While some visual trends might seem universal, it’s important to note that all of us live an experience that is ours. The viewer’s experiences and preconceived ideas are important to note. Blindly jumping on a trend can result in a misguided direction.

We have to know our audience in order to reach our audience.

Why Are They Important?

Life might be a lot easier if we just lived in a little bubble—but that’s often not how design works, especially if it’s of a commercial nature. If you’re creating for yourself, fine—you do you. If you’re designing for a market, however, it’s generally a good idea to be aware of what’s going on—what’s popular? What’s interesting? What aesthetic is resonating right now? And, most of all, how is your work communicating to this audience, based on this information?

That’s not to say we should blindly copy what’s popular. What I’m saying is, it’s a good idea to be aware of what’s going on. Then, we can play into this—make it our own. Even if you opt to go completely against what’s on trend right now, awareness could still make this approach even more impactful.

Examples of Design Trends

Back in the 80s, generous use of color (often saturated or pastels) and geometric influence were a popular aesthetic. It’s one that we’ve seen take on a bit of a nostalgic resurgence recently.

If, for example, we wanted to design something that plays into this feeling of nostalgia, we’d need to take note of what makes this aesthetic “tick”—what are the textbook visual cues that viewers would expect to see? If we don’t understand an aesthetic, we probably can’t capture it well.

The Value and Inspiration in the “Old”

But, trends come and trends go—we see it in all different kinds of art and media—and then sometimes aesthetics come back again.

Why even bother, if it’s not going to last?

Take a look at this work by Wassily Kandinsky, titled “Composition VIII”, from 1923. This geometric abstraction has always rather reminded me of the use of geometry that was popular in the 80s.

They’re certainly not the same—it’s safe to say Kandinsky’s process and intent likely varied (intensely) from that of a commercial design from 1985—but the experimentation with geometry, its movement when employed together and with color, is fundamental in both. Geometry can be very expressive—and beautiful.

My point is, aesthetics don’t necessarily “die”—in fact, they often have continued value, even after they’ve “had their day”.

I think there is a lot of value in observing art and design from the past—and that’s for practicing designers, not exclusively academics!

How Theory and Aesthetics Relate

A Successful Partnership

So, how do design trends and design principles relate?

I’d argue that they make a very valuable, successful partnership. When employed together, we potentially have a composition that is both well constructed and visually interesting in a particularly relevant way.

But, if we know the principles of design, why pay attention to trends at all?

Well, imagine a design that is well composed, but aesthetically out of touch. It might seem boring or uninteresting.

So, if we know an aesthetic, inside and out, why bother with theory at all?

Well, imagine relying on trends but not knowing quite how to establish hierarchy or emphasis in the composition. It could be a “pretty mess”.

One Example in Three Aesthetics

To further explore this idea, let’s observe the same design, remade three times, all with a different aesthetic direction. You’ll notice that, in terms of theory, the design itself isn’t all that different—nothing’s been “moved” (although it’s difficult not to touch any of the principles when you change a composition around!).

Here’s our initial design. I created a simple movie poster for a film called “The Design”.

Example 2

This second example uses vibrant colors and some varied typography. How does it visually communicate to you? What associations does this make you think of?

Example 3

And here’s another take on this design. Take note of the communicative qualities of the visuals—working from this perspective can make a difference.

Remember, however, that communicative aspects of design are larger than ourselves. We often need to think about the target audience and their perspective—not just our own (unless it’s personal work, of course).

One Example in Three Compositions

Now, let’s take the same premise and flip it around—the same aesthetic, but three different compositions. I’ll use the same imagery, colors, and typefaces, but I’ll change things up using the principles of design as my guide.

This time, I created a simple poster for a space documentary.

Example 2

Notice that the ratio and proximity of the elements in this design have been changed. This includes the relationship with the background photo.

Does this change how you “read” the information? Where do your eyes naturally “move”?

Example 3

And here’s the final example. This time, the balance is asymmetrical, and there’s more emphasis placed on the tagline.

There are plenty of things we could potentially do with this composition. Which did you think was most successful?

The point here is, the principles of design arm us with the theory to create a well-composed composition. This can generally be utilized and applied to any aesthetic, any project, any analysis.

Using Both to Build Your Project

Fabulous Form and Function

So, how do we use what we’ve discussed here—how do we employ both theory and aesthetics in a successful way?

Personally, I view the principles of design as my tools. They’re how I’m going to build this house.

Aesthetics help me figure out the floor plan. The principles are my means of creating that floor plan, but aesthetics have a lot to do with that process too—what is this house going to look like, and why? We generally don’t build a structure without intent and direction.

Inspiration as a Starting Point

Pick up design books. Read design blogs. Check out the portfolios of other artists. Observe the world around you—not only as a consumer, but as a creator, too.

When I start a new project, particularly in design or branding, I like to start with research. Don’t only look at the competitors—look at all sorts of things relevant to your audience. Be aware of what’s popular with them. Even if you’re doing personal work, you can gather content that inspires you—and then try to understand why.

If you want extra practice, try analyzing some of your favorite works. Where do you see the principles of design in action? What are the key parts of this aesthetic?

Here’s to Good Design!

Thank you for joining me in this exploration of design principles and design trends! I hope you enjoyed it and wish you all the best in your creative pursuits. Happy designing!

If you enjoyed this article, here are some others that you might enjoy!

Design TheoryApply Design Principles to Your Professional LifeDaisy Ein

Design TheoryApply Design Principles to Your Professional LifeDaisy Ein BrandingHow to Create Your Own Brand GuidelinesGrace Fussell

BrandingHow to Create Your Own Brand GuidelinesGrace Fussell FashionHow Fashion Influences DesignMelody Nieves

FashionHow Fashion Influences DesignMelody Nieves Adobe IllustratorThe Ultimate Guide to Adobe Illustrator SwatchesAndrei Stefan

Adobe IllustratorThe Ultimate Guide to Adobe Illustrator SwatchesAndrei Stefan Typography5 Typography Secrets to Transform Your DesignsGrace Fussell

Typography5 Typography Secrets to Transform Your DesignsGrace Fussell

{excerpt}

Read More