Dragons are scary, zombies are scary, and what’s more frightening than an angry zombie dragon? But it’s just one of all these fascinating creatures you can see in your mind! In this tutorial I’ll show you the process for creating a monster from scratch, from the idea, sketch and anatomy to the final clean lines. You’ll learn how to bring one of your great concepts to life, making it readable for others and ready to be re-created in any other form. By the way, you’ll also learn how to create a believable anatomy on the fly. You don’t need any software—a pencil and a few sheets of paper will be enough.

1. Define the Pose

Step 1

Having a nice design in your mind isn’t everything—your creature needs a base, a kind of skeleton to support it. The problem is it’s not easy to create a skeleton for something that doesn’t exist yet.

There’s a rule that can help us here. Pose makes a big part of the image—it’s far more important than details. It’s the first thing a viewer notices, so if it’s not interesting enough, your whole illustration will suffer. Here’s the advice: create an interesting pose without considering the design yet.

First, describe your design in terms of actions and emotions, like: “ready to attack”, “still”, “alert”, “disturbed”, “confident”, “shy”, “nonchalant”, “furious”, etc. Second, try to picture these terms with thick, messy lines. Don’t limit yourself to one pose—just transfer your elusive ideas to paper and see how they work.

For my zombie dragon I used the keywords:

- furious

- restless

- insane

- blinded with anger

So, that’s your assignment: draw a few lines that are furious, restless, insane, and blinded with anger. Sketch them on a small scale, don’t zoom in, and don’t add any details. Don’t judge, just draw them all, one by one.

Step 2

Now we need to elaborate these “lines of motion”. We’ve got spines and maybe heads, so it’s time to add some more to it. We don’t need a full skeleton yet, or any details. Just add a base for legs and wings, obeying the emotion.

Having a problem here? A basic body for our dragon will be built of these simple elements. Just use them, obeying the emotions and actions you have chosen.

- Head

- Wing

- Spine

- Hips

- Tail

- Neck

- Chest

- Front legs

- Hind legs

Step 3

The other criterion for concept art is to show the body features clearly, without concealing them by a complicated pose. Which of your sketches meet this requirement? Which are dynamic and interesting, but without covering important parts with a wing or neck? Choose a few, then decide which of them looks the closest to your vision.

- Dynamism: 2/5; Clarity: 1/5 = 3

- Dynamism: 3/5; Clarity: 5/5 = 8

- Dynamism: 4/5; Clarity: 3/5 = 7

- Dynamism: 3/5; Clarity: 3/5 = 6

- Dynamism: 1/5; Clarity: 5/5 = 6

Step 4

Once we’ve got a basic pose, we can polish it. It’s time to build a base for all the body features. This is the moment when we need to take a look at anatomy of the animal. With a dragon, it may be hard to find a good reference—every artist creates their own version. If you need some help, check my tutorial about dragons, paying special attention to the skeleton and joints. If you want to do it quickly, here’s a cheat sheet.

Use the previous sketch as a base and polish its lines, fixing less obvious structures.

Step 6

The pose is finished—that’s the first thing your viewers will see. How do you like it?

2. Refine the Guide Shapes

The pose still needs a bit of work. When you look at it now, it could be a fat pegasus, or some weird winged lion. We need to make the shapes more readable, so that the details have no influence on the “soul” of the illustration.

Step 1

We need poses for the smaller parts too. First, wings. To understand them better, check this tutorial. Also, my tutorial on bats may be helpful here.

Step 2

We need to define the head also. The position of the jaws adds a lot to the general emotion. To learn more about drawing dragon heads, check my tutorial on this topic. If you want to make it quickly, just follow these steps:

Step 3

We also need to define the exact position of the claws before going any further.

Step 4

The sketch is complete now. If you’re drawing traditionally, it’s good to redraw it on a bigger

scale on a new sheet. Use subtle strokes—the pose should not be visible

on the finished lineart.

3. Build the Dragon Anatomy—Skeleton

We’re entering dangerous territory now—we’re going to picture the anatomy of an animal that doesn’t exist. The good news is, with a settled pose it’s going to be very hard to break the illustration, no matter what you do now. So let’s build the skeleton, bone by bone.

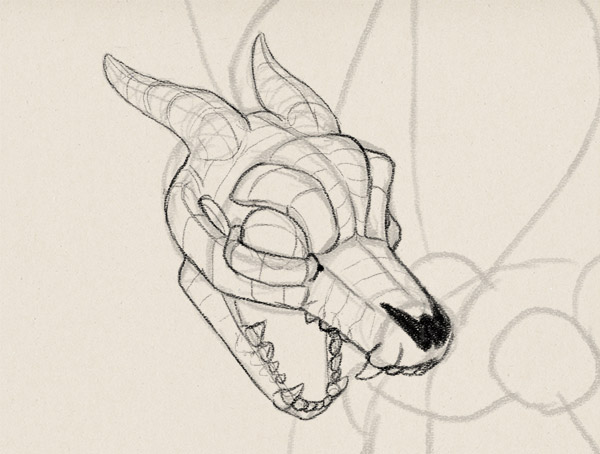

Step 1

The skull is the second most difficult and, in a visual sense, the most important part of the skeleton. To get it right it’s good to study real animal skulls first and then construct a dragon skull out of them. I’ve based my skull on big cats. Do you see how I used lines to define 3D forms? I’ve explained this trick in this tutorial.

Once again—if you’ve never drawn a skull in your life, don’t expect that you’ll be able to draw it now. Find a reference, analyze it, draw, then repeat with another picture. When you feel that you’ve understood these structures, you can go further and draw something without a reference—like the skull of non-existent creature.

Step 2

Draw the main part of the straight bones by surrounding the guide lines between “joints” with straight lines.

The forearms and calves need one more bone.

Step 3

Connect the bones with a thickening of the joint. Imagine the tip of the bone as a ball with a concave or convex top—it will help you in places where a 3D view is necessary.

Step 4

Claws can be done exactly the same way.

Step 5

Do you remember what I told you about the skull? Hips are the only bones that are even harder to draw. It’s because they don’t have clear top/bottom and side views. In other words, classic 2D views of hips won’t help you understand their shape.

I simplified the hip structure for you, but if it’s still too complicated, just get around it somehow—create a placeholder for it and then cover it with muscles or skin. This way you’ll finish the illustration without learning complicated stuff you won’t use any more.

Step 6

Let’s prepare the space for the ribcage. Draw a circle linking both arms and wings. The spine will be stuck to it on the back of the circle—use this point to draw a line connecting the shoulder girdle with the hips. In the front, draw a line that will make the sternum.

Step 7

Draw two clavicles between an arm and the top of the sternum.

Step 8

Here we’ve got a problem with the shoulder blades. An arm needs them to move, but wings are nothing but modified arms. Therefore, we need two pairs of scapulae! Again, this is a fantasy creature and you can just ignore this issue by adding only one pair, or even cover these bones later to avoid confusion. Draw the sternum made of two parts.

Step 9

Time for the spine. Draw it as a long, thin snake from the back of the skull to the tip of the tail.

Step 10

The spine is made of vertebrae. Each of them has a very complicated structure, but let’s start with something simple. Use two ellipses for the top and bottom of a vertebra. The neck and the end of the tail will have the longest vertebrae.

Step 11

Use the guide lines to sketch the vertebrae.

Step 12

Before we go any further, we need to define the thickness of the neck and tail. We can do it simply by drawing circles, big at the core and then smaller and smaller to the tip.

Step 13

Use the circles to draw the neck and tail. Don’t forget to define the sides!

Step 14

Let’s come back to the vertebrae. Prepare guide lines for the appendixes with a simple line ended with a circle.

Step 15

Stress the shape they have created. Ribs will be attached under the hind pair.

Step 16

Now things will be a bit different for the neck, back, and tail.

Back

Tail

Neck

Step 17

The neck needs special treatment. Add a pair of sharp, elongated appendixes.

Step 18

Clean the shapes.

Step 19

The ribcage is the last part we need to take care of. We can borrow it from any big animal, or just use this simplified scheme:

Start by defining the space the ribcage takes. Then draw the lines for the ribs, keeping in mind the bending points (black dots).

Step 20

Our skeleton is done! It looks pretty good and you can use it as it is, but I’ll show you how to make a complete zombie out of this. If your sketch has got messy by now, it’s good to copy it to a clean sheet.

4. Build the Dragon Anatomy—Muscles

Let’s bring some life—or death, actually—to our dragon. To make it easy we’re going to use a simplified pseudo-anatomy that will look proper to a layman, but without paying too much attention to its functionality. Our goal is to create a disintegrating body, with both bones and muscles visible, so we don’t need to make the musculature complete.

Step 1

Muscles are a kind of lever used to move a bone to one side or another. For this mechanism to work properly, we need to connect two bones with one or more muscles.

Create levers on the skeleton. They don’t need to be very accurate, so just use your intuition! Imagine a kind of string pulling the bones closer to each other.

Step 2

Draw muscles all along the lines you’ve just sketched. They mostly bulge in the middle and taper at the ends. You don’t need to include all the muscles—it’s a zombie, after all. Leave the most eye-catching of the bones uncovered—for example, we’ve spent a lot of time on the spine and it would be a shame to cover such a fascinating structure.

Step 3

Time to tear the wings. You should find it easy, just remember about gravity.

Step 4

Clean the lines and add any details you like. The lineart is finished! If you want to, you can shade it to finish it as a complete illustration.

This Is Not the End!

We’ve created an undead dragon, but we’re not finished yet! This lineart will be used for the next part of this tutorial, in which we’ll create a complete digital concept art in Adobe Photoshop. Stay tuned!

{excerpt}

Read More