Travelers are increasingly being denied entry to the United States as border officials hold them accountable for messages, images and video on their devices sent by other people.

It’s a bizarre set of circumstances that has seen countless number of foreign nationals rejected from the U.S. after friends, family or even strangers send messages, images or videos over social media sites like Facebook and Twitter, and encrypted messaging apps like WhatsApp, which are then downloaded to the traveler’s phone.

The latest case saw a Palestinian national living in Lebanon and would-be Harvard freshman denied entry to the U.S. just before the start of the school year.

Immigration officers at Boston Logan International Airport are said to have questioned Ismail Ajjawi, 17, for his religion and religious practices, he told the school newspaper The Harvard Crimson. The officers who searched his phone and computer reportedly took issue with his friends’ social media activity.

Ajjawi’s visa was canceled and he was summarily deported — for someone else’s views.

The United States border is a bizarre space where U.S. law exists largely to benefit the immigration officials who decide whether or not to admit or deny entry to travelers, and few protect the travelers themselves. Both U.S. citizens and foreign nationals alike are subject to unwarranted searches and few rights to free speech, and many have limited access to legal counsel.

That has given U.S. border officials a far wider surface area to deny entry to travelers — sometimes for arbitrary reasons.

On a typical day, U.S. Customs & Border Protection processes 1.13 million passengers by plane, sea and land and deny entry to more than 760 people. Sometimes a denial is clear, such as a past criminal conviction or the wrong documentation. But all too often, no specific reasons are given, and there are no grounds to appeal.

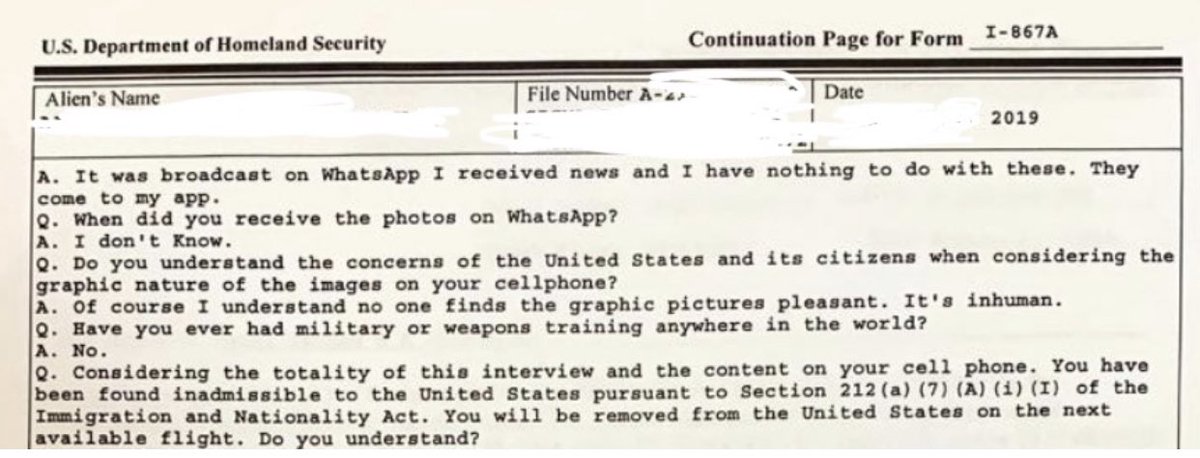

A U.S. immigration form describing why a traveler was denied entry to the U.S. (Image: Abed Ayoub/Twitter)

CBP also claims to have what critics say is broadly unconstitutional powers to search travelers’ phones — including those of U.S. citizens — at the border without needing a warrant. Last year, CBP searched 30,000 travelers’ devices — a four-times increase since 2015 — without any need for reasonable suspicion.

Complicating matters, the Trump administration in June began to demand that foreigners who apply for U.S. visas disclose their social media handles and profiles. Some 15 million are expected to fall under the new rule.

A spokesperson for Customs & Border Protection did not comment.

Summer Lopez, senior director of free expression programs at PEN America, a human rights nonprofit, said in a statement that the immigration policy on social media “demonstrates all too well the damage these ill-conceived policies can do.”

“That should not be the price of entrance to the U.S., let alone that one’s friends should have to censor themselves as well,” said Lopez.

But Ajjawi’s denied entry is not an isolated case.

Abed Ayoub, legal and policy director at the American-Arab Anti-Discrimination Committee, said device searches and subsequent denials of entry had become the “new normal” over the past year.

“We hear about this happening to Arab students and Muslim students coming into the U.S. today,” he told TechCrunch. Although all travelers are subject to having their devices searched, Ayoub said the government was “holding [the Arab and Muslim] community to a different level” than other backgrounds.

Ayoub said he’s had clients that have been turned away at the border for content found in their WhatsApp messages.

“It’s probably the most popular app in the Middle East,” he said. Because WhatsApp automatically downloads received images and videos to a user’s phone, any questionable content — even sent unsolicitedly — under a border official’s search could be enough to deny the traveler entry.

In one tweet, Ayoub posted a photo of an expedited removal form from one of his clients — also a student with U.S. visa — who was denied entry for an image he received in a WhatsApp group. The student strenuously denied any personal connection to the images and argued it had been automatically saved to his phone. The border official wrote that as a result of the device search the student was “inadmissible” to the U.S. The student was only a couple of semesters away from graduating, but a rejection meant the student can no longer return to the U.S.

“This is part of the backdoor ‘Muslim ban,’ ” Ayoub said, referring to a controversial executive order signed by President Trump in January 2017, which barred citizens from seven predominantly Muslim countries entry to the U.S.

“We don’t hear of other other individuals being denied because of WhatsApp or because of what’s on the social media,” he said.

Correction: an earlier version of this report said the Harvard student was Lebanese. He is a Palestinian national living in Lebanon.