A lot can change in a year. Not when you’re Equifax.

The credit rating giant, one of the largest in the world, was trusted with some of the most sensitive data used by banks and financiers to determine who can be lent money. But the company failed to patch a web server it knew was vulnerable for months, which let hackers crash the servers and steal data on 147 million consumers. Names, addresses, Social Security numbers and more — and millions more driver license and credit card numbers were stolen in the breach. Millions of British and Canadian nationals were also affected, sparking a global response to the breach.

It was “one of the most egregious examples of corporate malfeasance since Enron,” said Senate Democratic leader Chuck Schumer at the time.

Yet, a year on from following the devastating hack that left the company reeling from a breach of almost every American adult, the company has faced little to no action or repercussions.

In the aftermath, the company’s response to the breach was chaotic, sending consumers scrambling to learn if they were affected but were instead led into a broken site that was vulnerable to hacking. And when consumers were looking for answers, Equifax’s own Twitter account sent concerned users to a site that easily could have been a phishing page had it not been for a good samaritan.

Yet, the company went unpunished. In the end, Equifax was in law as much a victim as the 147 million Americans.

“There was a failure of the company, but also of lawmakers,” said Mark Warner, a Democratic senator, in a call with TechCrunch. Warner, who serves Virginia, was one of the first lawmakers to file new legislation after the breach. Alongside his Democratic colleague, Sen. Elizabeth Warren, the two senators said their bill, if passed, would hold credit agencies accountable for data breaches.

“With Equifax, they knew for months before they reported, so at what point is that violating securities laws by not having that notice?,” said Warner.

“There was a failure of the company, but also of lawmakers.”

Sen. Mark Warner (D-VA)

“The message sent to the market is ‘if you can endure some media blowback, you can get through this without serious long-term ramifications’, and that’s totally unacceptable,” he said.

Lawmakers held hearings and grilled the company’s former chief executive, Richard Smith, who retired with his full $90 million retirement package, adding insult to injury. Equifax further shuffled its executive suite, including the hiring of a new chief information security officer Jamil Farshchi and former lawyer turned “chief transformation officer” Julia Houston to oversee “the company’s response to the cybersecurity incident.”

Equifax declined to make either executive available for interview or comment when reached by TechCrunch, but Equifax spokesperson Wyatt Jefferies said protecting customer data is the company’s “top priority.”

But there’s not much to show for it beyond superficial gestures of free credit monitoring — provided by Equifax, no less — and a credit locking app which, unsurprisingly, had its own flaws. In the year since, the company has spent more than $240 million — some $50 million was covered by cyber-insurance. That’s a drop in the ocean to more than $3 billion in revenue in the year since, according to quarterly earnings filings — or more than $500 million in profits. And although Equifax’s stock price initially collapsed in the weeks following, the price bounced back.

Financially, the company looks almost as healthy as it’s ever been. But that may change.

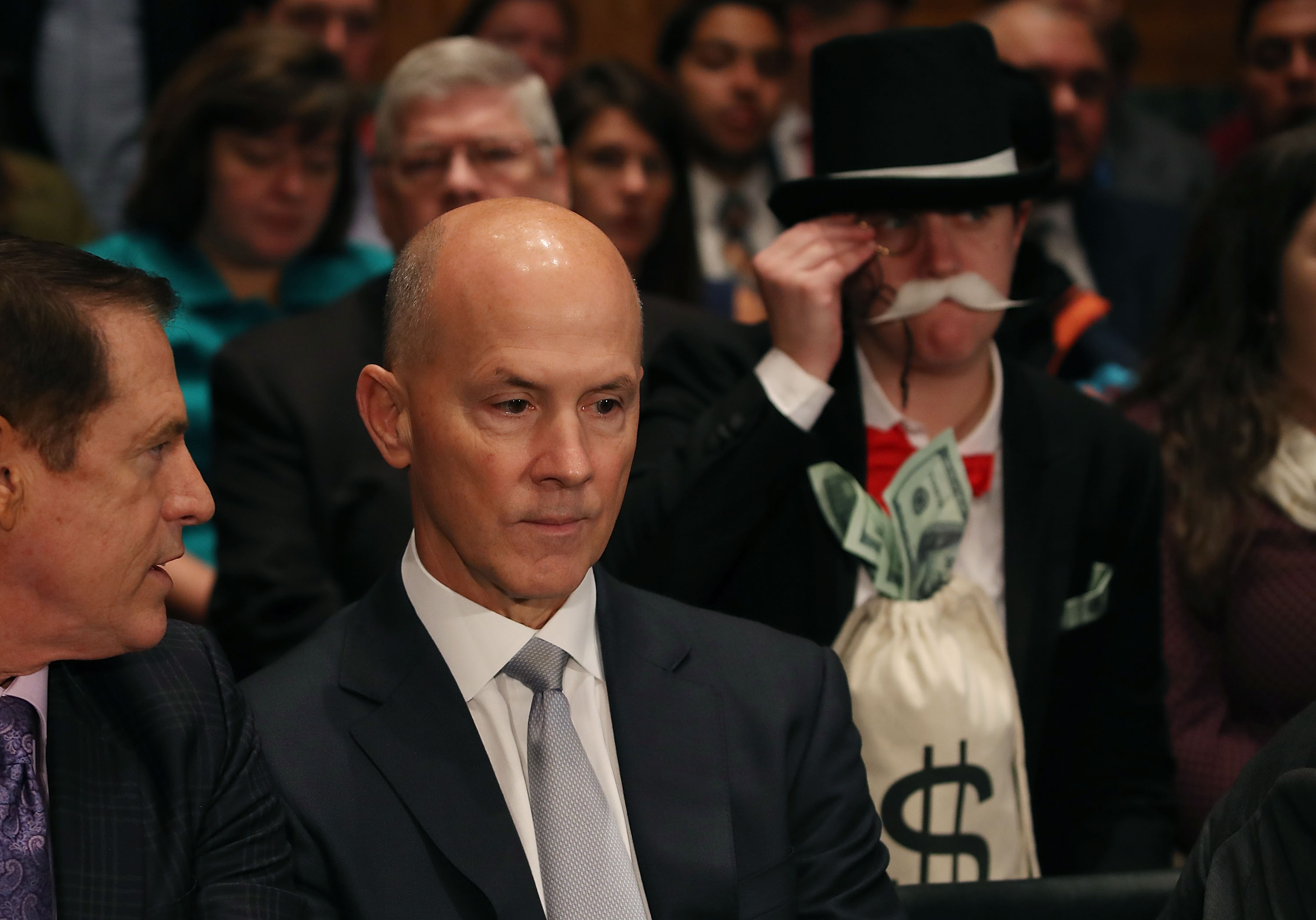

Former Equifax chief executive Richard Smith prepares to testify before the lawmakers. Smith later retired after hackers broke into the credit reporting agency and made off with the personal information of nearly 145 million Americans.

Earlier this year, the company asked a federal judge to reject claims from dozens of banks and credit unions for costs taken to prevent fraud following the data breach. The claims, if accepted, could force Equifax to shell out tens of millions of dollars — perhaps more. The hundreds of class action suits filed to date have yet to hit the courts, but historically even the largest class action cases have resulted in single dollar amounts for the individuals affected.

And when the credit agent giant isn’t fighting the courts, federal regulators have shown little interest in pursuit of legal action.

An investigation launched by a former head of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, responsible for protecting consumers from fraud, sputtered after the new director reportedly declined to pursue the company. And, although the company is under investigation by the Federal Trade Commission for the second time this decade, fines are likely to be limited — if levied at all.

Warren sent a letter Thursday to the heads of both agencies lamenting their lack of action.

“Companies like Equifax do not ask the American people before they collect their most sensitive information,” said Warren. “This information can determine their ability to access credit, obtain a job, secure a home loan, purchase a car, and make dozens of other transactions that are critical to their personal financial security.”

“The American people deserve an update on your investigations,” she said.

To date, only the Securities and Exchange Commission has brought charges — not for the breach itself, but against three former staffers for allegedly insider trading.

Escaping any local action, Equifax agreed with eight states, including New York and California, to take further cybersecurity steps and measures to prevent another breach, escaping any fines or financial penalties.

“The American people deserve an update on your investigations”

Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-MA)

Warner blamed much of the inaction to the patchwork of data breach laws that vary by state.

“We’ve got different laws and you don’t have any standard, and part of the challenge around the data breach is that every industry wants to be exempted,” said Warner. It’s not a partisan issue, he said, but one where every industry — from telecoms to retail — wants to be exempt from the law.

“If we really want to improve our business cyber-hygiene, you have got to have consequences for failing to keep up those cyber-hygiene standards,” he said.

It’s a tough sell to posit Equifax, which fluffed almost every step of the breach process, before and after its disclosure, as a victim. While the millions affected can take solace in the beating Equifax got in the press, those demanding regulatory action might be in for a disappointingly long wait.