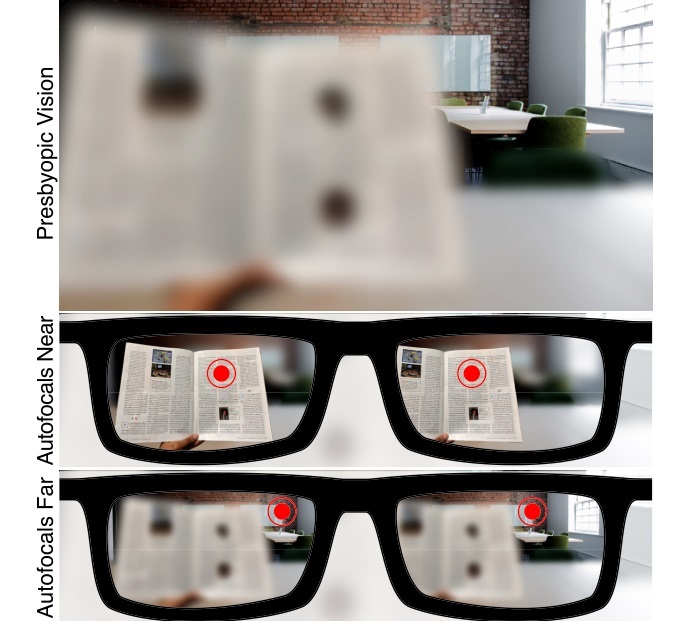

The complex optics involved with putting a screen an inch away from the eye in VR headsets could make for smartglasses that correct for vision problems. These prototype “autofocals” from Stanford researchers use depth sensing and gaze tracking to bring the world into focus when someone lacks the ability to do it on their own.

I talked with lead researcher Nitish Padmanaban at SIGGRAPH in Vancouver, where he and the others on his team were showing off the latest version of the system. It’s meant, he explained, to be a better solution to the problem of presbyopia, which is basically when your eyes refuse to focus on close-up objects. It happens to millions of people as they age, even people with otherwise excellent vision.

There are, of course, bifocals and progressive lenses that bend light in such a way as to bring such objects into focus — purely optical solutions, and cheap as well, but inflexible, and they only provide a small “viewport” through which to view the world. And there are adjustable-lens glasses as well, but must be adjusted slowly and manually with a dial on the side. What if you could make the whole lens change shape automatically, depending on the user’s need, in real time?

That’s what Padmanaban and colleagues Robert Konrad and Gordon Wetzstein are working on, and although the current prototype is obviously far too bulky and limited for actual deployment, the concept seems totally sound.

Padmanaban previously worked in VR, and mentioned what’s called the convergence-accommodation problem. Basically, the way that we see changes in real life when we move and refocus our eyes from far to near doesn’t happen properly (if at all) in VR, and that can produce pain and nausea. Having lenses that automatically adjust based on where you’re looking would be useful there — and indeed some VR developers were showing off just that only 10 feet away. But it could also apply to people who are unable to focus on nearby objects in the real world, Padmanaban thought.

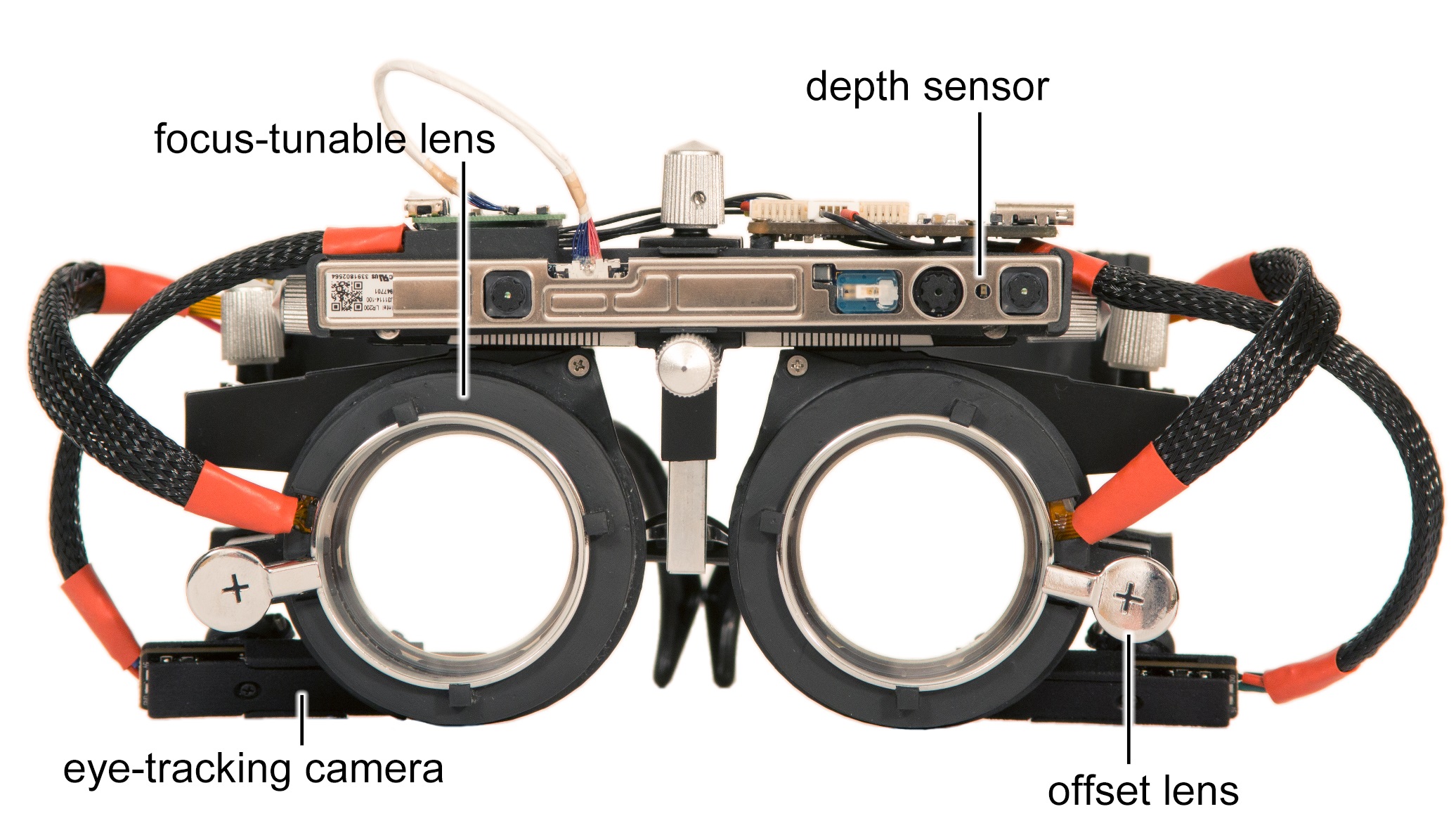

This is an old prototype, but you get the idea.

It works like this. A depth sensor on the glasses collects a basic view of the scene in front of the person: a newspaper is 14 inches away, a table three feet away, the rest of the room considerably more. Then an eye-tracking system checks where the user is currently looking and cross-references that with the depth map.

Having been equipped with the specifics of the user’s vision problem, for instance that they have trouble focusing on objects closer than 20 inches away, the apparatus can then make an intelligent decision as to whether and how to adjust the lenses of the glasses.

Having been equipped with the specifics of the user’s vision problem, for instance that they have trouble focusing on objects closer than 20 inches away, the apparatus can then make an intelligent decision as to whether and how to adjust the lenses of the glasses.

In the case above, if the user was looking at the table or the rest of the room, the glasses will assume whatever normal correction the person requires to see — perhaps none. But if they change their gaze to focus on the paper, the glasses immediately adjust the lenses (perhaps independently per eye) to bring that object into focus in a way that doesn’t strain the person’s eyes.

The whole process of checking the gaze, depth of the selected object and adjustment of the lenses takes a total of about 150 milliseconds. That’s long enough that the user might notice it happens, but the whole process of redirecting and refocusing one’s gaze takes perhaps three or four times that long — so the changes in the device will be complete by the time the user’s eyes would normally be at rest again.

“Even with an early prototype, the Autofocals are comparable to and sometimes better than traditional correction,” reads a short summary of the research published for SIGGRAPH. “Furthermore, the ‘natural’ operation of the Autofocals makes them usable on first wear.”

The team is currently conducting tests to measure more quantitatively the improvements derived from this system, and test for any possible ill effects, glitches or other complaints. They’re a long way from commercialization, but Padmanaban suggested that some manufacturers are already looking into this type of method and despite its early stage, it’s highly promising. We can expect to hear more from them when the full paper is published.