The current world speed record for riding a bike down a straight, flat road was set in 2012 by a Dutch team, but the Swiss have a plan to topple their rivals — with a little help from machine learning. An algorithm trained on aerodynamics could streamline their bike, perhaps cutting air resistance by enough to set a new record.

Currently the record is held by Sebastiaan Bowier, who in 2012 set a record of 133.78 km/h, or just over 83 mph. It’s hard to imagine how his bike, which looked more like a tiny landbound rocket than any kind of bicycle, could be significantly improved on.

But every little bit counts when records are measured down a hundredth of a unit, and anyway, who knows but that some strange new shape might totally change the game?

To pursue this, researchers at the École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne’s Computer Vision Laboratory developed a machine learning algorithm that, trained on 3D shapes and their aerodynamic qualities, “learns to develop an intuition about the laws of physics,” as the university’s Pierre Baqué said.

“The standard machine learning algorithms we use to work with in our lab take images as input,” he explained in an EPFL video. “An image is a very well-structured signal that is very easy to handle by a machine-learning algorithm. However, for engineers working in this domain, they use what we call a mesh. A mesh is a very large graph with a lot of nodes that is not very convenient to handle.”

“The standard machine learning algorithms we use to work with in our lab take images as input,” he explained in an EPFL video. “An image is a very well-structured signal that is very easy to handle by a machine-learning algorithm. However, for engineers working in this domain, they use what we call a mesh. A mesh is a very large graph with a lot of nodes that is not very convenient to handle.”

Nevertheless, the team managed to design a convolutional neural network that can sort through countless shapes and automatically determine which should (in theory) provide the very best aerodynamic profile.

“Our program results in designs that are sometimes 5-20 percent more aerodynamic than conventional methods,” Baqué said. “But even more importantly, it can be used in certain situations that conventional methods can’t. The shapes used in training the program can be very different from the standard shapes for a given object. That gives it a great deal of flexibility.”

That means that the algorithm isn’t just limited to slight variations on established designs, but it also is flexible enough to take on other fluid dynamics problems like wing shapes, windmill blades or cars.

The tech has been spun out into a separate company, Neural Concept, of which Baqué is the CEO. It was presented today at the International Conference on Machine Learning in Stockholm.

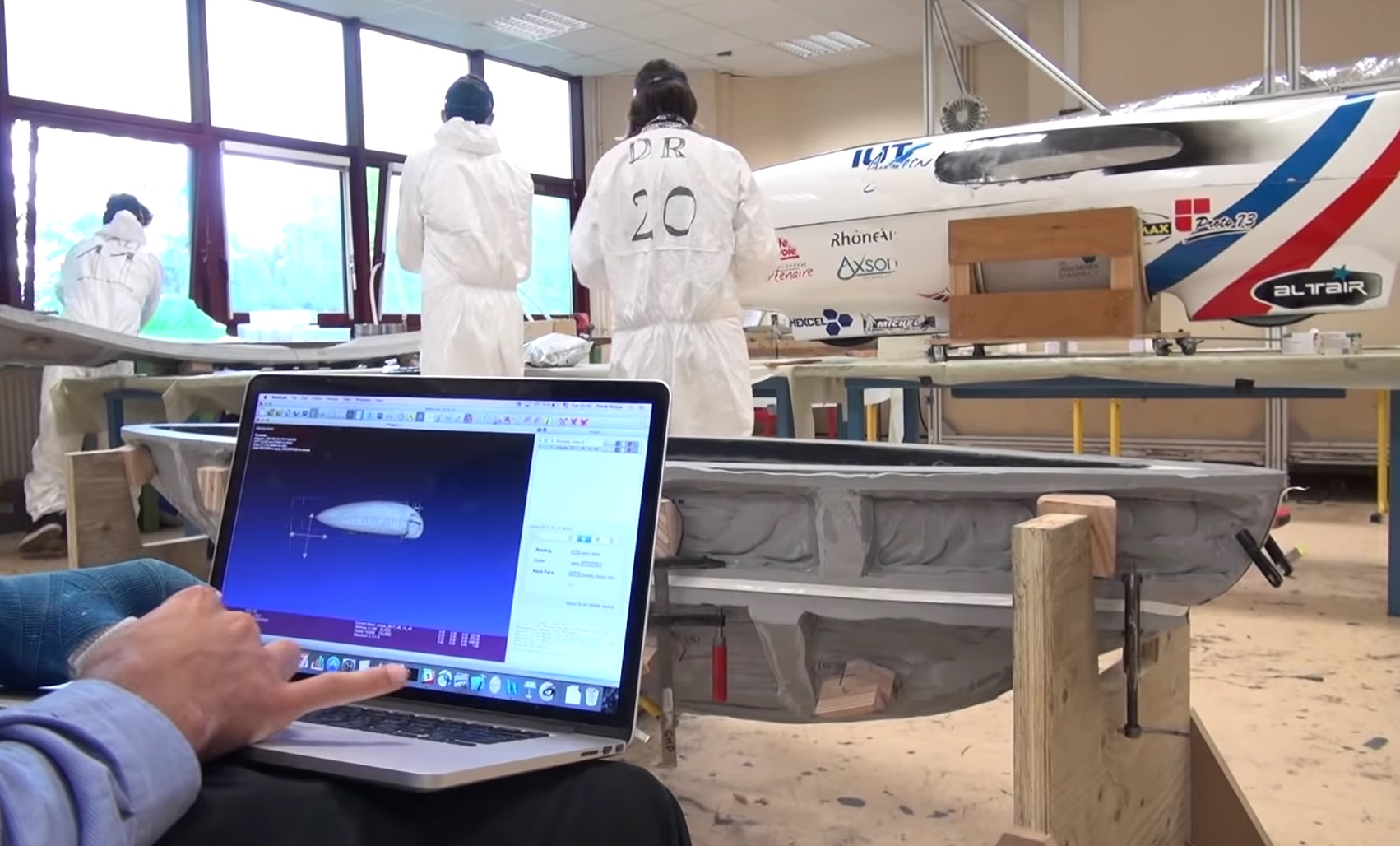

A team from the Annecy University Institute of Technology will attempt to apply the computer-honed model in person at the World Human Powered Speed Challenge in Nevada this September — after all, no matter how much computer assistance there is, as the name says, it’s still powered by a human.