A gas grill rules. But the real debate should be whether charcoal is necessary at all…

Category: Tech news

hacking,system security,protection against hackers,tech-news,gadgets,gaming

Grilling Over Charcoal Is Objectively, Scientifically Better Than Grilling Over Gas

Cooking on a gas grill is more convenient than cooking with charcoal. It’s also a lot less special.

Roland’s tiny R-07 recorder is better than your phone’s recorder app

In an era when the smartphone can do everything, why do you need a standalone audio recorder? Roland, makers of music gear, might have an answer.

Their R-07 voice recorder is about as big as an original iPod and is designed for music recording, practice and playback. It features two microphones on top as well as an auxiliary microphone input. It also includes a headphone jack and supports Bluetooth.

As a recorder, the R-07 is a single-touch marvel. You record by turning it on and pressing the center button. It records to MicroSD card and can create up to 96 kHz 24-bit WAVs and 320 kbps MP3s. It runs on USB power or two AA batteries.

A Scene mode makes the R-07 a bit more interesting. It has built-in limiters and low cut, essentially features that will make voices crisper. Further, you can set it to “Music Long” to record longer performances while using less drive space.

Rehearsal mode lets you hear live audio through audio playback, a great feature for budding musicians.

Finally, you can control up to four devices at once via Bluetooth, allowing you to mic various members of a band, for example.

The R-07 costs an acceptable $199 and is shipping now. While it doesn’t beat a massive recorder with dual mics and XLR inputs like the Zoom H6 in terms of versatility, in terms of portability and sound quality — not to mention music-friendly features — the R-07 is a great alternative to the Voice Memos app on your phone.

Uber launches a Jump e-bike pilot in London, one year on from winning taxi license appeal

After admitting it had to modify some of its Jump electric bikes to fix braking issues — the same problem that had halted Lyft’s e-bike business — Uber is getting back on its bike, so to speak. Almost one year after nearly getting driven off London’s streets completely by losing its taxi operating license, Uber today announced the launch of Jump e-bikes in London. The service is kicking off with a pilot of 350 bikes in the borough of Islington, with plans to expand to more areas of the city in the coming months.

If you are in the catchment, Jump Bikes will now appear as an option in your Uber app alongside UberPool, UberX and public transportation data — which was added three weeks ago.

Pricing for the dockless Jump bikes is modelled on how Jump works in the U.S.: it costs £1 to unlock a bike, and then £0.12 per minute to ride it, with your first five minutes free. The electric pedal-assist responds to pedal pressure, and can give a boost to help you ride up to 15 miles per hour. If you park a bike outside of the allowed range (currently, Islington), you get a warning on the app. And if you leave the bike parked there, you get a £25 fine.

“There is now one more transport alternative for the 3.5 million people who use the Uber app in the capital,” said Jamie Heywood, Uber’s GM for Northern and Eastern Europe. “Over time, it’s our goal to help people replace their car with their phone by offering a range of mobility options – whether cars, bikes or public transport, all in the Uber app.”

Ridesharing companies like Uber and Lyft, built on hailing cars through apps, have been gradually incorporating other forms of transportation on to their platforms to diversify what they offer to consumers, and to provide a more open and accessible face to local regulators.

In urban areas, sometimes taking cars is excessive or impractical because of the distances covered, or the traffic situation, or because the passenger wants to do something more active than sit in the back of a Prius. (It’s not the only one: As we reported a couple of weeks ago, Uber’s soon-to-be-Middle Eastern business, Careem, which it’s buying for $3.1 billion, has also been working on buying a bike startup.)

That has led to adding other “vehicles” like bikes and scooters, as well as public transportation for those who want to walk a little, as well.

The bigger idea is that even in cases where the operator — Uber, in this case — is not getting a cut on the ride (as in the case of public transportation), or actually making very little on the ride while also taking on more overhead (as it does with owning bike fleets where average rides are likely to be less than $10), it’s helping create a habit: It wants to be the app a consumer turns to for any transportation-related need, groundwork that it has to have in place to help ensure longer-term viability (and now, also, to keep public investors confident that Uber will ultimately be able to tip itself into the black and continue to grow… not a sure bet for everyone).

But it’s not just about consumer choice. It was almost a year ago that Uber won a hotly contested appeal in the London courts to get an extension of its vehicle-operating license in London (which had been snapped away from it by angry regulators) while it worked on fixing some of the issues that it had with its service: adding more environment-friendly, and car traffic congestion-reducing, options like e-bikes is also part of that effort.

The bumpy road for micromobility

Micromobility — the term for two-wheeled vehicles and the short rides and small fees that are typically collected around them — has had something of a bumpy road in London, not unlike other markets.

For starters, we still do not have any on-demand scooter services (electric or otherwise) running widely in the capital. Part of the reason is that the U.K.’s Department of Transportation and Transport for London (the city’s local authority) have not yet determined whether and how to change electric scooters’ classification for open-road use.

Currently, electric scooters are classified as light electric vehicles and are illegal on both roads and sidewalks, so can only be used on private property, making any wide commercial rollouts impossible.

To date, the only electric scooter businesses that we have seen launched in the U.K. have been pilots in closed campuses, like the Bird scooter service in the Olympic Village started last year. I’d be curious to know how widely those scooters are used: every time I’ve been to the area, I’ve seen far more scooters parked than I’ve seen moving.

There are a number of electric scooter services already available in other markets in Europe — Paris, where you might find kids giving each other lifts on them, or couples romantically co-riding on single vehicles (très Parisienne!), is apparently one of the largest e-scooter markets in the world now. But these are facing other problems, such as malfunctioning vehicles, and vast, clutter-ific oversupply. That’s not stopping money from pouring into the startups, though!

Bikes have also had their issues — wonky gears, you might say. A number of the companies that confidently launched services a year ago have either collapsed or significantly curtailed operations. Some are recapitalising and trying once more on a different footing. Mobike, which is currently raising money to complete a spin-off from its Chinese parent, also wants to add alternative forms of transport, which could include e-bikes and scooters, to its fleet.

However, electric bikes — despite some notable hiccups in the U.S., such as Lyft’s service halt, executive changes and layoffs — are a story that has yet to be fully played out.

If you were to walk through many parts of the city today, you’d likely see multiple Lime e-bikes alongside the plethora of other shared bikes that can be picked up and used on-demand.

The city is sprawling enough that walking might take a bit too long, congested enough that any motorised car or bus also doesn’t inspire, and with a good enough amount of inclines that regular bikes face a barrier from anyone but the most confident or regular cyclist: the perfect environment for e-bikes, some might say.

That’s given Uber a big fillip to move ahead with the Jump launch here now.

“We’re excited to bring JUMP bikes to Islington, our first launch in London. With our electric bikes, we hope to encourage more people to try an environmentally friendly way to get across the city,” said Christian Freese, general manager of JUMP, EMEA, in a statement.

“Our JUMP bikes have been designed with safety in mind, with a sturdy frame and a bright red colour that makes them visible to other road users. The app explains features of the bike before your first trip so you can ride confidently. We encourage everyone to think about wearing a helmet, follow all traffic laws and brake early and gradually.”

Unlike its original forays into car-sharing, Uber’s move with bikes has been made with playing nice in mind.

“We’re working hard to make Islington an attractive and easier place to walk and cycle. We’re pleased to welcome JUMP to Islington – bike sharing offers a simple way for many residents, workers and visitors to get around quickly, cheaply and conveniently,” said Claudia Webbe, a councillor in the borough of Islington who is also executive member for Environment and Place. “Shared electric bikes are accessible to many people of different ages and fitness levels, and can help encourage even more people to switch to cycling, which is healthier and more environmentally friendly.”

How the EU’s Far Right Will Boost Google, Facebook, and Amazon

Trump’s former campaign guru said he would unite Europe’s nationalists and show them how to fight Big Tech. Instead, they’ve dismissed Bannon, embraced Big Tech—and are poised to expand their ranks in Parliament.

Netflix’s ‘Rim of the World’ Shows Where Sci-Fi Is Headed

One good thing about the streaming wars? The return of ’80s-style adventure flicks.

REI Anniversary Sale: 29 Best Summer Outdoor Deals for 2019

REI’s big Anniversary Sale is still on through Memorial Day. It’s the best time of the year to pick up all the wetsuits, mountain bikes, and coolers that you’ll need. These are our favorite new and remaining deals in stock.

Hiking or Camping? Take the Bus to the Trail This Summer

Transit agencies and nonprofits are teaming up to expand access to parks and recreation areas.

Airbnb and New York City Reach a Truce on Home-Sharing Data

Airbnb agreed to turn over information on 17,000 residences, so city officials can look for signs of illegal short-term rentals.

The Danger in Assange’s Charges, a Memory Experiment, and More News

Catch up on the most important news from today in two minutes or less.

Following a report about misleading ads placed by anti-abortion groups, Google Ads updates its policies

Starting next month, Google will enforce new policies for ads related to abortion in the United States, United Kingdom and Ireland. Google will now require advertisers that want to run ads with abortion-related keywords to apply for certification as an organization that does, or does not, provide abortions. If their ads are approved, they will run with an automatically-generated disclaimer identifying which category they fall into.

The announcement of the new policies comes less than two weeks after the Guardian reported that Google had provided $150,000 in free advertising through its grant program for non-profits to the Obria Group, an anti-abortion group that runs crisis pregnancy centers, or organizations that provide services like pregnancy tests, ultrasounds and counseling, but ultimately seek to deter people from getting abortions.

According to the Guardian, the ads placed by the Obria Group were misleading and made it appear as though their centers provide abortions, a tactic used by many crisis pregnancy centers. Google’s new policies also come as several states, including Missouri, Alabama, Georgia, Mississippi, Kentucky and Ohio have passed, or are seeking to pass, extremely restrictive laws limiting access to abortion.

Google did not mention crisis pregnancy centers or the new legislation in its policy update announcement, but the new rules may help limit the appearance of misleading ads. Before running ads with abortion-related keywords, advertisers must first submit an application to Google saying whether or not they provide abortions. If it is approved, their ads will run with automatically-generated in-ad disclaimers that says the advertiser either “provides abortions” or “does not provide abortions.” The disclosures will appear on the ads across all Search ad formats.

Google’s existing policies about abortion-related ads, which list countries where such ads are not allowed, or only allowed to run on a limited basis, will remain in place. (Abortion-related ads don’t appear on the Google Display Network.)

Google has already been criticized for allowing misleading ads related to abortion, including five years ago after an investigation by NARAL Pro-Choice American into ads for crisis pregnancy centers, the same issue reported by the Guardian this month. Misinformation about abortion is rampant, so this is a step in the right direction, but it remains to be seen how effective Google’s new policy will be in combating a long-standing problem.

A young entrepreneur is building the Amazon of Bangladesh

At just 26, Waiz Rahim is supposed to be involved in the family business, having returned home in 2016 with an engineering degree from the University of Southern California. Instead, the young entrepreneur is plotting to build the Amazon of Bangladesh.

Deligram, Rahim’s vision of what e-commerce looks like in Bangladesh, a country of nearly 180 million, is making progress, having taken inspiration from a range of established tech giants worldwide, including Amazon, Alibaba and Go-Jek in Indonesia.

It’s a far cry from the family business. That’s Rahimafrooz, a 55-year-old conglomerate that is one of the largest companies in Bangladesh. It started out focused on garment retail, but over the years its businesses have branched out to span power and energy and automotive products while it operates a retail superstore called Agora.

During his time at school in the U.S., Rahim worked for the company as a tech consultant whilst figuring out what he wanted to do after graduation. Little could he have imagined that, fast-forward to 2019, he’d be in charge of his own startup that has scaled to two cities and raised $3 million from investors, one of which is Rahimafrooz.

Deligram CEO Waiz Rahim [Image via Deligram]

“My options after college were to stay in U.S. and do product management or analyst roles,” Rahim told TechCrunch in a recent interview. “But I visited rural areas while back in Bangladesh and realized that when you live in a city, it’s easy to exist in a bubble.”

So rather than stay in America or go to the family business, Rahim decided to pursue his vision to build “a technology company on the wave of rising economic growth, digitization and a vibrant young population.”

The youngster’s ambition was shaped by a stint working for Amazon at its Carlsbad warehouse in California as part of the final year of his degree. That proved to be eye-opening, but it was actually a Kickstarter project with a friend that truly opened his mind to the potential of building a new venture.

Rahim assisted fellow USC classmate Sam Mazumdar with Y Athletics, which raised more than $600,000 from the crowdsourcing site to develop “odor-resistant” sports attire that used silver within the fabric to repel the smell of sweat. The business has since expanded to cover underwear and socks, and it put Rahim’s mind to work on what he could do by himself.

“It blew my mind that you can build a brand from scratch,” he said. “If you are good at product design and branding, you could connect to a manufacturer, raise money from backers and get it to market.”

On his return to Bangladesh, he got Deligram off the ground in January 2017, although it didn’t open its doors to retailers and consumers until March 2018.

E-commerce through local stores

Deligram is an effort to emulate the achievements of Amazon in the U.S. and Alibaba in China. Both companies pioneered online commerce and turned the internet into a major channel for sales, but the young Bangladeshi startup’s early approach is very different from the way those now hundred-billion-dollar companies got started.

Offline retail is the norm in Bangladesh and, with that, it’s the long chain of mom and pop stores that account for the majority of spending.

That’s particularly true outside of urban areas, where such local stores almost become community gathering points, where neighbors, friends and families run into each other and socialize.

Instead of disruption, working with what is part of the social fabric is more logical. Thus, Deligram has taken a hybrid approach that marries its regular e-commerce website and app with offline retail through mom and pop stores, which are known as “mudir dokan” in Bangladesh’s Bengali language.

A customer can order their product through the Deligram app on their phone and have it delivered to their home or office, but a more popular — and oftentimes logical — option is to have it sent to the local mudir dokan store, where it can be collected at any time. But beyond simply taking deliveries, mudir dokans can also operate as Deligram retailers by selling through an agent model.

That’s to say that they enable their customers to order products through Deligram even if they don’t have the app, or even a smartphone — although the latter is increasingly unlikely with smartphone ownership booming. Deligram is proactively recruiting mudir dokan partners to act as agents. It provides them with a tablet and a physical catalog that their customers can use to order via the e-commerce service. Delivery is then taken at the store, making it easy to pick up, and maintaining the local network.

“We’ll tell them: ‘Right now, you offer a few hundred products, now you have access to 15,000,’ ” the Deligram CEO said.

Indeed, Rahim sees this new digital storefront as a key driver of revenue for mudir dokan owners. For Deligram, it is potentially also a major customer acquisition channel, particularly among those who are new to the internet and the world of smartphone apps.

This offline-online model — known by the often-buzzy industry term “omnichannel” — isn’t new, but in a world where apps and messaging is prevalent, reaching and retaining users is challenging, particularly in emerging markets.

“It’s not easy to direct people to a website today, and the app-first approach has made it hard,” Rahim said. “We looked at how companies in Indonesia and India overcame these challenges.”

In particular, he studied the work of Go-Jek in Indonesia, which uses an agent model to push its services to nascent internet users, and Amazon India, which leans heavily on India’s local “kirana” stores for orders and deliveries.

In Deligram’s case, the mudir dokan picks up sales commission as well as money for every delivery that is sent to their store. Home deliveries are possible, but the lack of local infrastructure — “turn right at the blue house, left at the white one, and my place is third from the left,” is a common type of direction — makes finding exact locations difficult and inefficient, so an additional cost is charged for such requests.

E-commerce startups often struggle with last-mile because they rely on a clutch of logistics companies to fulfill orders. In a rare move for an early-stage company, Deligram has opted to run its entire logistics process in-house. That obviously necessitates cost and likely provides significant growing pains and stress, but, in the long term, Rahim is betting that a focus on quality control will pay out through higher customer service and repeat buyers.

A prospective Deligram customer flips through a hard copy of the company’s product brochure in a local store [Image via Deligram]

Startups on the rise in Bangladesh

Rahim’s timing is impeccable. He returned to Bangladesh just as technology was beginning to show the potential to impact daily life. Bangladesh has posted a 7% rise in GDP annually every year since 2016, and with an estimated 80 million internet users, it has the fifth-largest online population on the planet.

“We are riding on a lot of macro trends; we’re among the top five based on GDP growth and have the world’s eighth-largest population,” Rahim told TechCrunch. “There are 11 million people in middle income — that’s growing — and our country has 90 million people aged under 30.”

“An index to track the growth of young people would be [capital city] Dhaka… you can just see the vibrancy with young people using smartphones,” he added.

That’s an ideal storm for startups, and the country has seen a mix of overseas entrants and local ventures pick up speed. Alibaba last year acquired Daraz, the Rocket Internet-founded e-commerce service that covers Pakistan, Bangladesh, Myanmar, Sri Lanka and Nepal, while the Chinese giant also snapped up 20% of bKash, a fintech venture started from Brac Bank as part of the regional expansion of its Ant Financial affiliate.

Uber, too, is present, but it is up against tough local opposition, as is the norm in Asian markets.

That’s because Bangladesh’s most prominent local startups are in ride-hailing. Pathao raised more than $10 million in a funding round that closed last year and was led by Go-Jek, the Indonesia-based ride-hailing firm valued at more than $9 billion that’s backed by the likes of Tencent and Google. Pathao is reportedly on track to raise a $50 million Series B this year, according to Deal Street Asia.

Pathao is one of two local companies that competes alongside Uber in Bangladesh [Image via Pathao]

Its chief rival is Shohoz, a startup that began in ticketing but expanded to rides and services on-demand. Shohoz raised $15 million in a round led by Singapore’s Golden Gate Ventures, which was announced last year.

Deligram has also pulled in impressive funding numbers, too.

The startup announced a $2.5 million Series A raise at the end of March, which Rahim wrote came from “a network of institutional and angel investors;” such is the challenge of finding a large check for a tech play in Bangladesh. The investors involved included Skycatcher, Everblue Management and Microsoft executive Sonia Bashir Kabir. A delighted Rahim also won a check from Rahimafrooz, the family business.

That’s not a given, he said, admitting that his family did initially want him to go to work with their business rather than pursuing his own startup. In that context, contributing to the round is a major endorsement, he said.

Rahimafrooz could be a crucial ally in future fundraising, too. Despite an improving climate for tech companies, Bangladesh’s top startups are still finding it tough to raise money, especially with overseas investors that can write the larger checks that are required to scale.

“I think the biggest challenge is branding. Every time I speak with new investors, I have to start by explaining where Bangladesh is, or the national metrics, not even our business,” Pathao CEO Hussain Elius told TechCrunch.

“There’s a legacy issue. Bangladesh seems like a country which floods all the time and the garment sector going down — that’s a part of the story but not the full story. It’s also an incredible country that’s growing despite those challenges,” he added.

Pathao is reportedly on track to raise a $50 million Series B this year, according to Deal Street Asia. Elius didn’t address that directly, but he did admit that raising growth funding is a bigger challenge than seed-based financing, where the Bangladesh government helps with its own fund and entrepreneurial programs.

“It’s hard for us as we’re the first ones out there, but it’ll be easier for the ones who’ll follow on,” he explained.

Still, there are some optimistic overseas watchers.

“We remain enthusiastic about the rapidly expanding set of opportunities in Bangladesh,” said Hian Goh, founding partner of Singapore-based VC firm Openspace — which invested in Pathao.

“The country continues to be one of the fastest-growing economies in the world, underpinned by additional growth in its garments manufacturing sector. This has blossomed into an expanding middle class with very active consumption behavior,” Goh added.

Growth plans

With the pain of fundraising put to the side for now, the new money is being put to work growing the Deligram business and its network into more parts of Bangladesh, and the more challenging urban areas.

Geographically, the service is expanding its agent reach into five more cities to give it a total of seven locations nationwide. That necessitates an increase in logistics and operations to keep up with, and prepare for, that new demand.

Deligram workers in one of the company’s warehouses [Image via Deligram]

Rahim said the company had handled 12,000 orders to date as of the end of March, but that has now grown past 20,000 indicating that order volumes are rising. He declined to provide financial figures, but said that the company is on track to increase its monthly GMV volume by six-fold by the end of this year. Electronics, phones and accessories are among its most popular items, but Deligram also sells apparel, daily items and more.

Interestingly, and perhaps counter to assumptions, Deligram started in rural areas, where Rahim saw there was less competition but also potentially more to learn through a more early-adopter customer base. That’s obviously one major challenge when it comes to growth, and now the company is looking at urban expansion points.

On the product side, Deligram is in the early stages of piloting consumer financing using its local store agents as the interface, while Rahim teased “exciting IOT R&D projects” that he said are in the planning stage.

Ultimately, however, he concedes that the road is likely to be a long one.

“Over the last 18-20 years, modern retail hasn’t made much progress here,” Rahim said. “It accounts for around 2.5% of total retail, e-commerce is below 1% and the long tail local stores are the rest.”

“People will eventually shift, but I think it’ll take five to eight years, which is why we provide the convenience via mom and pop shops,” he added.

Food delivery startup Dahmakan eats up $5M for expansion in Southeast Asia

It’s harvest season for Southeast Asia’s full-stack food delivery startups. Following on from Singapore’s Grain raising $10 million, so Malaysia-based Dahmakan today announced a $5 million financing round of its own.

The money takes the startup to $10 million raised to date — its last round as $2.6 million last year — and it comes via new investors U.S-based Partech Partners and China’s UpHonest Capital and existing backers Y-Combinator, Atami Capital and the former CEO of Nestlé who was an angel investor. The round was closed earlier this year but is now being announced alongside this expansion play.

It’s been a busy couple of years for the company, which was founded in 2015 by former execs from Rocket Internet’s FoodPanda service. Dahmakan — which means “Have you eaten?” in Malay — graduated Y Combinator in 2017 and it expanded to Thailand last year through an acquisition, so what’s on the menu for 2019?

It is going all in on ‘cloud kitchen’ model of using unwanted retail space to cook up meals specifically for digital orders, which is entirely its business since it handles all processes in house rather than through a marketplace model.

Already, in its home town of Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, Dahmakan has introduced ‘satellite’ hubs that will allow it to serve customers located in different parts of the city more efficiently. The service already fares better than rivals like FoodPanda, Grab Food and (in Thailand) GoJek’s GetFood service because customers order ahead of time from a fixed menu with scheduled delivery times, but there’s room to do better and more.

“The way that we are thinking about it is that we are 18 months ahead of the competition in terms of the cloud kitchen model. Most are only starting to build out clusters of mini kitchens (150sqft) or so without leveraging too much AI in terms of product development, procurement or automation in machinery,” Dahmakan COO and co-founder Jessica Li told TechCrunch.

“What we’ve figured out is how to scale food production for thousands of deliveries while maintaining quality and keeping costs at 30 percent below comparable restaurant prices,” she added, explaining that the company plans to add “new brands and new products” using the satellite hub approach.

A serving of Ayam Penyet, Indonesian smashed chicken

Dahmakan is looking to extend its reach in Southeast Asia, too.

Li said the immediate priority is domestic growth in Malaysia with the service set to expand in Penang and Johor Bharu during the third quarter of this year. Beyond that, she revealed that Dahmakan plans to move into Singapore and Indonesia before the end of 2019.

Food delivery is quickly becoming the new ride-hailing war in Southeast Asia as Grab and Go-Jek, which have raised the most money in the region, pour capital into space. Quite why they are doing so isn’t entirely clear. Food could be a channel for loyalty (if such a thing can exist in incentive-led verticals) and user engagement for ride-hailing or other parts of their so-called “super app” services, but, either way, it is certainly distorting the market by flooding users with promotions.

That’s not necessarily a bad thing for startups like Dahmakan and Grain which have grown in a more sustainable and responsible manner. They benefit from more people using food delivery in general, while they may also become attractive acquisition targets in the future.

Like Grain, Dahmakan puts a focus on healthy eating, which stands in contrast to the typical junk food orders that others in the space serve through their marketplace of restaurants. That certainly helps them stand out among certain audiences, and it’ll be interesting to see what new products and brands that Dahmakan is hatching to capitalize on the flood of attention food delivery is seeing..

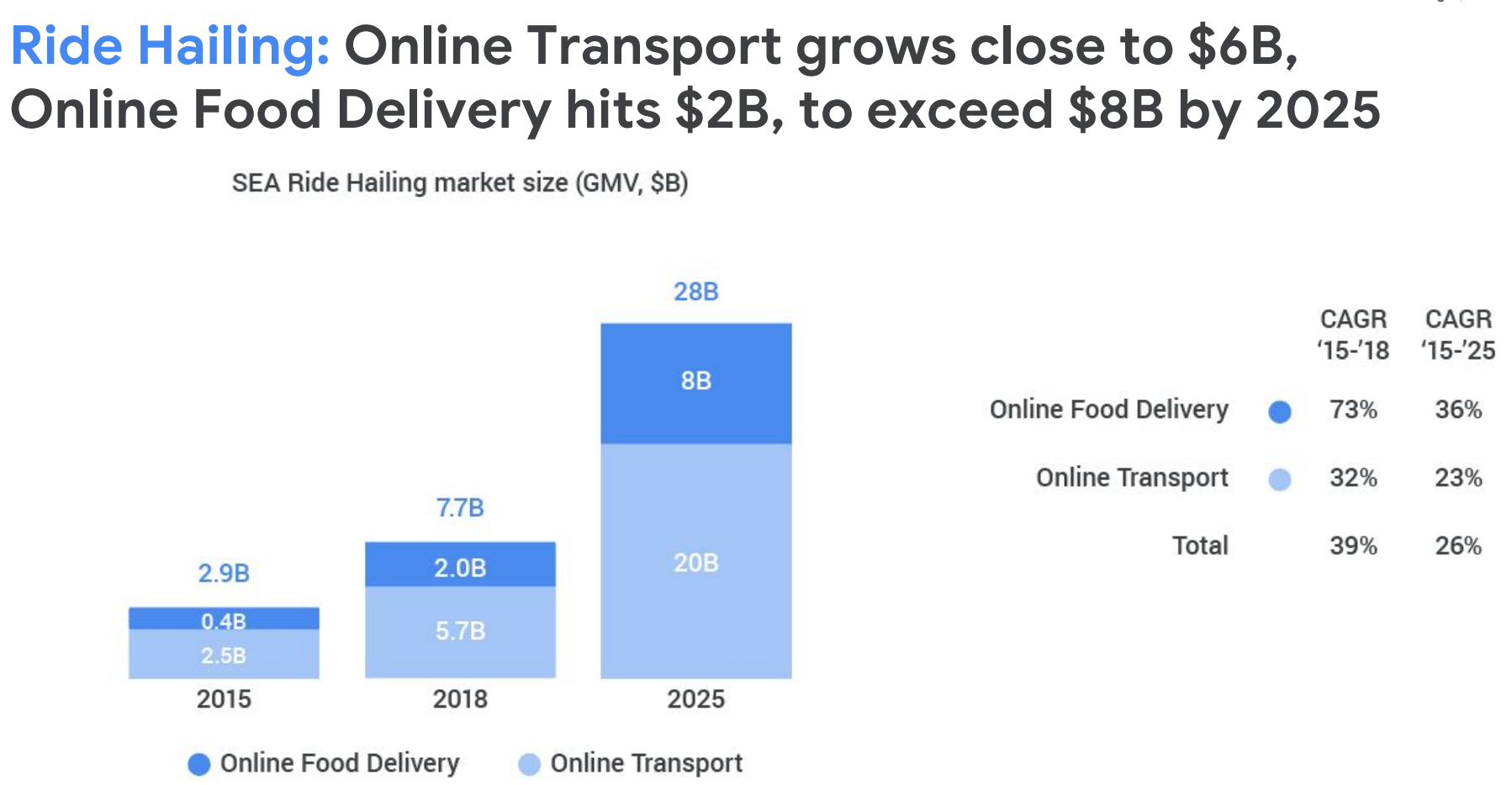

This is certainly only the start. A Google-Temasek report on Southeast Asia published last year forecasts that the region’s food delivery market will grow from an estimated $2 million last year to $8 billion in 2025. That four-fold prediction is larger than the growth forecast for ride-hailing, although the latter is larger.

“That’s faster than any other region even China,” Li said.

A report from Google and Temasek predicts huge growth for ride-hailing and food delivery services in Southeast Asia

Famed founder Daphne Koller tells it straight: “With most drugs, we do not understand why they work”

Daphne Koller doesn’t mind hard work. She joined Stanford University’s computer science department in 1995, spending the next 18 years there in a full-time capacity before cofounding the online education giant Coursera, where she spent the following four years and remained co-chairman until last month. Koller then spent a little less than two years at Alphabet’s longevity lab, Calico, as its first chief computing officer.

It was there that Koller was reminded of her passion for applying machine learning to improve human health. She was also reminded of what she doesn’t like, which is wasted effort, something that the drug development industry — slow to understand the power of computational methods for analyzing biological data sets — has been plagued by for years.

In fairness, those computational methods have also gotten a whole lot better more recently. Little wonder that last year, Koller spied the opportunity to start another company, a drug development company called Insitro that has since raised $100 million in Series A funding, including from GV, Andreessen Horowitz and Bezos Expeditions, among others. As notably, the company recently partnered with Gilead Sciences to find medicines to treat a liver disease called nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) because of all the related human data that Gilead has amassed over time.

Later, Insitro may target even bigger epidemics, including perhaps Alzheimer’s disease or Type 2 diabetes. Certainly, it has reason to feel optimistic about what it can accomplish. As Koller told a group of rapt attendees at an event hosted by this editor a few days ago, “We’re now at a moment in history where a confluence of technologies emerged all at around the same time allow really large and interesting and disease-relevant data sets to be produced in biology. In parallel, we see . . . machine learning technologies that are able to make sense of that data and come up with novel insights that can hopefully cure disease.”

It all sounds like talk we’ve heard before in recent years, but coming from Koller, one gets the sense that we’re finally getting close, despite the mysteries of human biology. Below are some excerpts from Koller’s interview with journalist Sarah McBride of Bloomberg. You can also watch their conversation below.

On why Insitro struck a partnership with Gilead (beyond that it could prove lucrative, with up to $1 billion in milestones attached to successfully developing targets for NASH):

There are fairly broad categories that our technology is well-suited for. We’re really interested in creating what you might call disease-in-a-dish models — places where diseases are complex, where we really haven’t had a good model system, where typical animal models that have been used [for years, including testing on mice] just aren’t very effective — and creating those ‘in vitro’ models to generate very large amounts of data that can be interpreted using machine learning.

There’s a whole slew of diseases that lend themselves to this type of approach. NASH was one of them, so partly it was the suitability of our technology to this disease, and partly it was that Gilead was just a really good partner for it because they have a whole bunch of human data from some of the clinical trials that have been running [which give us] access to two complementary data sources. One is what happens to the disease in large human cohorts, and one is what happens when you look at what the disease does in vitro, in the dish, then see if we can use what we see in the dish using machine learning to predict what we see in the human.

On how Insitro views data differently than big pharma companies:

Pharma companies say, ‘We have lots of data.’ And you say, ‘What kinds of data do you have?’ And it turns out they have dribs and drab of data, each stored on a separate spreadsheet in someone else’s laptop. There’s metadata that isn’t even recorded. For them, it’s like, ‘Yeah, I did the experiment and obviously I recorded what I had to because it doesn’t make sense to throw it away,’ but they don’t think of it as something you build a company on top of.

We come at it a completely different way. We say, ‘This is the problem that you’d like to solve. If only we had a model that could tell us the result of this experiment without having to do the experiment, because it’s costly or complicated or even impossible [because it would involve perturbing a living human’s gene].’ Well, machine learning has gotten really good at building predictive models if you give it the right data to train the model. So we’re in the business of actually building data for the sole purpose of training machine learning models. We think of [these models] like little crystal balls that would allow you to avoid doing [these more expensive or complicated] experiments.

On the impact of the National Institutes of Health’s “All of Us” research program, which is an effort to gather data from one million or more people living in the U.S. to accelerate research and improve health in part by logging individual differences in lifestyle, environment, and biology:

I would say if anything that the U.S. is a little late to the game on this one. There have been a number of national cohorts have already been generated in different countries; the two that are currently best developed are in Iceland and in the U.K, but there’s also one in Finland and one in Ireland and even in Estonia, where they’ve taken a large population from within that country and measured their genetics, but also measured a whole lot of properties about those people, including blood biomarkers and urine biomarkers and behavioral aspects and physical aspects and imaging. And so what you have now (in these countries) is a dataset that tells you, ‘Nature perturbed this gene,’ and, ‘We see this effect on the human.’

[In the UK, specifically, where they started their program five years ago and recruited 500,000 volunteers who agreed to physical and cognitive and blood pressure testing and images of the brain and the abdomen, among other things] it’s an incredibly rich data set [from which] discoveries are coming along on pretty much a weekly basis.

… This is valuable not just primarily for gene therapies but just as a way of identifying targets that actually make a difference, because most drugs that go into clinical trials fail. And by most, I mean 95 percent. And most drugs fail because they are targeting the wrong things. They are targeting proteins or genes that do not affect the disease they are supposed to affect. The recent, very visible failures of Alzheimer’s drug trials — actually several of them in a row — were almost certainly because the protein they were targeting, called amyloid beta, is just not the right causal factor in the disease.

On what researchers can do now with stem cells that would have been impossible even a few years ago:

[There are now] tools that have enabled the creation of not only large amounts of data but large amounts of biologically relevant data. So we used to do experiments on cancer cell lines . . . but it’s not a very disease relevant model. Today, we can take a small sample of skin cells and use what’s called the Yamanaka factor, to reprogram those cells to stem cell status, which are the cells that exist effectively in the womb. And those cells are capable of differentiating themselves into neural cells or liver cells or cardiac cells, and those are very disease relevant because they represent human biology; you can take those cells now from patients and from healthy people and see if there are differences in how they appear.

Readers, we could feature more of the transcript here, but we highly suggest watching the conversation with Koller. If you use this text as a leaping off point, you’ll want to start listening at around the 13-minute mark. It’s definitely worth the time to hear what she has to say, including about cystic fibrosis, spinal muscular dystrophy in babies, and why the “mouse models” we’ve long relied on for a wide number of seemingly ubiquitous diseases “range from bad to really, really bad.” Hope you enjoy it.

SoFar Sounds house concerts raises $25M, but bands get just $100

Tired of noisy music venues where you can hardly see the stage? SoFar Sounds puts on concerts in people’s living rooms where fans pay $15 to $30 to sit silently on the floor and truly listen. Nearly 1 million guests have attended SoFar’s more than 20,000 gigs. Having attended a half dozen of the shows, I can say they’re blissful…unless you’re a musician to pay a living. In some cases, SoFar pays just $100 per band for a 25 minute set, which can work out to just $8 per musician per hour or less. Hosts get nothing, and SoFar keeps the rest, which can range from $1100 to $1600 or more per gig — many times what each performer takes home. The argument was that bands got exposure, and it was a tiny startup far from profitability.

Today, SoFar Sounds announced it’s raised a $25 million round led by Battery Ventures and Union Square Ventures, building on the previous $6 million it’d scored from Octopus Ventures and Virgin Group. The goal is expansion — to become the de facto way emerging artists play outside of traditional venues. The 10-year-old startup was born in London out of frustration with pub-goers talking over the bands. Now it’s throwing 600 shows per month across 430 cities around the world, and over 40 of the 25,000 artists who’ve played its gigs have gone on to be nominated for or win Grammys. The startup has enriched culture by offering an alternative to late night, dark and dirty club shows that don’t appeal to hard-working professionals or older listeners.

But it’s also entrenching a long-standing problem: the underpayment of musicians. With streaming replacing higher priced CDs, musicians depend on live performances to earn a living. SoFar is now institutionalizing that they should be paid less than what gas and dinner costs a band. And if SoFar suck in attendees that might otherwise attend normal venues or independently organized house shows, it could make it tougher for artists to get paid enough there too. That doesn’t seem fair given how small SoFar’s overhead is.

By comparison, SoFar makes Uber look downright generous. A source who’s worked with SoFar tells me the company keeps a lean team of full-time employees who focus on reserving venues, booking artists, and promotion. All the volunteers who actually put on the shows aren’t paid, and neither are the venue hosts, though at least SoFar pays for insurance. The startup has previously declined to pay first-time SoFar performers, instead providing them a “high-quality” video recording of their gig. When it does pay $100 per act, that often amounts to a tiny shred of the total ticket sales.

“SoFar, however, seems to be just fine with leaving out the most integral part: paying the musicians” writes musician Joshua McClain. “This is where they willingly step onto the same stage as companies like Uber or Lyft?—?savvy middle-men tech start-ups, with powerful marketing muscle, not-so-delicately wedging themselves in-between the customer and merchant (audience and musician in this case). In this model, everything but the service-provider is put first: growth, profitability, share-holders, marketers, convenience, and audience members?—?all at the cost of the hardworking people that actually provide the service.” He’s urged people to #BoycottSoFarSounds

A deeply reported KQED expose by Emma Silvers found many bands were disappointed with the payouts, and didn’t even know SoFar was a for-profit company. “I think they talk a lot about supporting local artists, but what they’re actually doing is perpetuating the idea that it’s okay for musicians to get paid shit,” Oakland singer-songwriter Madeline Kenney told KQED.

SoFar CEO Jim Lucchese, who previously ran Spotify’s Creator division after selling it his music data startup The Echo Nest and has played SoFar shows himself, declares that “$100 buck for a showcase slot is definitely fair” but admits that “I don’t think playing a SoFar right now is the right move for every type of artist.” He stresses that some SoFar shows, especially in international markets, are pay-what-you-want and artists keep “the majority of the money”. The rare sponsored shows with outside corporate funding like one for the Bohemian Rhapsody film premier can see artists earn up to $1500, but these are a tiny fraction of SoFar’s concerts.

Otherwise, Lucchese says “the ability to convert fans is one of the most magical things about SoFar” referencing how artists rely on asking attendees to buy their merchandise or tickets for their full-shows and follow them on social media to earn money. He claims that if you pull out what SoFar pays for venue insurance, performing rights organizations, and its full-time labor, “a little over half the take goes to the artists.” Unfortunately that makes it sound like SoFar’s few costs of operation are the musicians’ concern. As McClain wrote, “First off, your profitability isn’t my problem.”

Now that it has ample funding, I hope to see SoFar double down on paying artists a fair rate for their time and expenses. Luckily, Lucchese says that’s part of the plan for the funding. Beyond building tools to help local teams organize more shows to meet rampant demand, he says “Am I satisfied that this is the only revenue we make artists right now? Abslutely not. We want to invest more on the artist side.” That includes better ways for bands to connect with attendees and turn them into monetizable fans. Even just a better followup email with Instagram handles and upcoming tour dates could help.

We don’t expect most craftspeople to work for “exposure”. Interjecting a middleman like SoFar shouldn’t change that. The company has a chance to increase live music listening worldwide. But it must treat artists as partners, not just some raw material they can burn through even if there’s always another act desperate for attention. Otherwise musicians and the empathetic fans who follow them might leave SoFar’s living rooms empty.