The software can help developers constrain their creations so they don’t make bad decisions.

Category: Tech news

hacking,system security,protection against hackers,tech-news,gadgets,gaming

Inside Apple’s High-Flying Bid to Become a Streaming Giant

With Ron Moore’s space-race drama “For All Mankind”, Apple is betting on marquee names and lush production to get its TV+ service off the ground. Can it achieve orbit?

So Long, Supply Drops: *Call of Duty* Ditches Loot Boxes

In the upcoming *Modern Warfare*, players will have to unlock all weapons and attachments through gameplay.

Trump’s Pelosi Tweet Tops This Week’s Internet News Roundup

The president’s attack didn’t quite go over as planned. Also, Lady Gaga wants to know what Fortnite is.

Cars Aren’t Going Anywhere, and More Transportation News This Week

Plus, we investigate a new, tiny jet engine for cargo-touting drones, and check out Volvo’s first electric car.

6 Best Camera Accessories for Android and iPhone (2019)

Assemble a photo studio you can carry in a backpack or messenger bag.

How to Pick the Best Roku: A Guide to Each Model (2019)

There are 7 Rokus for sale, and the differences between them are confusing. We break down exactly which Roku is best for your TV.

Computers Are Learning to Read—But They’re *Still* Not So Smart

A tool called BERT can now outperform us on advanced reading-comprehension tests. It’s also revealed how far AI has to go.

The Beats Powerbeats Pro Are $50 Off Right Now

Our favorite wireless workout buds are down to $250 to $200 right now.

How to Control the Privacy of Your Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and Snapchat Posts

Whether it’s Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, or Snapchat, lock down who can see what you’re up to.

Apple’s China stance makes for strange political alliances, as AOC and Ted Cruz slam the company

In a rare instance of bipartisanship overcoming the rancorous discord that’s been the hallmark of the U.S. Congress, senators and sepresentatives issued a scathing rebuke to Apple for its decision to take down an app at the request of the Chinese government.

Signed by Senators Ron Wyden, Tom Cotton, Marco Rubio, Ted Cruz, and Congressional Representatives Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Mike Gallagher and Tom Malinowski, the letter was written to “express… strong concern about Apple’s censorship of apps, including a prominent app used by protestors in Hong Kong, at the request of the Chinese government.”

Tim Cook gets a letter from @RonWyden @SenTomCotton @marcorubio @AOC @tedcruz @RepGallagher & @Malinowski re: China censorship. pic.twitter.com/dJlEAlheMX

— Jessica Smith (@JessicaASmith8) October 18, 2019

In 2019, it seems the only things that can unite America’s clashing political factions are the decisions made by companies in one of its most powerful industries.

At the heart of the dispute is Apple’s decision to take down an app called HKMaps that was being used by citizens of the island territory to track police activity.

For several months protestors have been clashing with police in the tiny territory over what they see as the undue influence being exerted by China’s government in Beijing over the governance of Hong Kong. Citizens of the former British protectorate have enjoyed special privileges and rights not afforded to mainland Chinese citizens since the United Kingdom returned sovereignty over the region to China on July 1, 1997.

“Apple’s decision last week to accommodate the Chinese government by taking down HKMaps is deeply concerning,” the authors of the letter wrote. “We urge you in the strongest terms to reverse course, to demonstrate that Apple puts values above market access, and to stand with the brave men and women fighting for basic rights and dignity in Hong Kong.”

Apple has long positioned itself as a defender of human rights (including privacy and free speech)… in the United States. Abroad, the company’s record is not quite as spotless, especially when it comes to pressure from China, which is one of the company’s largest markets outside of the U.S.

Back in 2017, Apple capitulated to a request from the Chinese government that it remove all virtual private networking apps from the App Store. Those applications allowed Chinese users to circumvent the “Great Firewall” of China, which limits access to information to only that which is approved by the Chinese government and its censors.

Over 1,100 applications have been taken down by Apple at the request of the Chinese government, according to the organization GreatFire (whose data was cited in the Congressional letter). They include VPNs, and applications made for oppressed communities inside China’s borders (like Uighurs and Tibetans).

Apple isn’t the only company that’s come under fire from the Chinese government as part of their overall response to the unrest in Hong Kong. The National Basketball Association and the gaming company Blizzard have had their own run-ins resulting in self-censorship as a result of various public positions from employees or individuals affiliated with the sports franchises or gaming communities these companies represent.

However, Apple is the largest of these companies, and therefore the biggest target. The company’s stance indicates a willingness to accede to pressure in markets that it considers strategically important no matter how it positions itself at home.

The question is what will happen should regulators in the U.S. stop writing letters and start making legislative demands of their own.

AI is helping scholars restore ancient Greek texts on stone tablets

Machine learning and AI may be deployed on such grand tasks as finding exoplanets and creating photorealistic people, but the same techniques also have some surprising applications in academia: DeepMind has created an AI system that helps scholars understand and recreate fragmentary ancient Greek texts on broken stone tablets.

These clay, stone or metal tablets, inscribed as much as 2,700 years ago, are invaluable primary sources for history, literature and anthropology. They’re covered in letters, naturally, but often the millennia have not been kind and there are not just cracks and chips but entire missing pieces that may comprise many symbols.

Such gaps, or lacunae, are sometimes easy to complete: If I wrote “the sp_der caught the fl_,” anyone can tell you that it’s actually “the spider caught the fly.” But what if it were missing many more letters, and in a dead language, to boot? Not so easy to fill in the gaps.

Doing so is a science (and art) called epigraphy, and it involves both intuitive understanding of these texts and others to add context; one can make an educated guess at what was once written based on what has survived elsewhere. But it’s painstaking and difficult work — which is why we give it to grad students, the poor things.

Coming to their rescue is a new system created by DeepMind researchers that they call Pythia, after the oracle at Delphi who translated the divine word of Apollo for the benefit of mortals.

The team first created a “nontrivial” pipeline to convert the world’s largest digital collection of ancient Greek inscriptions into text that a machine learning system could understand. From there it was just a matter of creating an algorithm that accurately guesses sequences of letters — just like you did for the spider and the fly.

PhD students and Pythia were both given ground-truth texts with artificially excised portions. The students got the text right about 57% of the time — which isn’t bad, as restoration of texts is a long and iterative process. Pythia got it right… well, 30% of the time.

But! The correct answer was in its top 20 answers 73% of the time. Admittedly that might not sound so impressive, but you try it and see if you can get it in 20.

The truth is the system isn’t good enough to do this work on its own, but it doesn’t need to. It’s based on the efforts of humans (how else could it be trained on what’s in those gaps?) and it will augment them, not replace them.

Pythia’s suggestions may not be perfectly right on the first try very often, but it could easily help someone struggling with a tricky lacuna by giving them some options to work from. Taking a bit of the cognitive load off these folks may lead to increases in speed and accuracy in taking on remaining unrestored texts.

The paper describing Pythia is available to read here, and some of the software they developed to create it is in this GitHub repository.

Adam Neumann planned for his children and grandchildren to control WeWork

WeWork co-founder Adam Neumann didn’t plan for his family’s control of WeWork to end at his death but instead expected to pass that control to future generations of Neumanns, too, says Business Insider.

The outlet reports that in a speech Neumann gave to employees in January of this year, footage of which it says it has viewed, Neumann is seen saying that WeWork isn’t “just controlled — we’re generationally controlled.” He reportedly goes on to say that while the five children he shares with wife Rebekah Neumann “don’t have to run the company,” they “do have to stay the moral compass of the company.”

According to BI, Neumann even invoked his future grandchildren, telling those gathered: “It’s important that one day, maybe in 100 years, maybe in 300 years, a great-great-granddaughter of mine will walk into that room and say, ‘Hey, you don’t know me; I actually control the place. The way you’re acting is not how we built it,’” he said.

These may sound like more outlandish proclamations from Neumann, who has a flair for the dramatic. (Talking to Fast Company earlier this year, he compared WeWork to a rare jewel, asking, “Do you know how long it takes a diamond to be created?”)

But before WeWork began coming apart at the seams, Neumann had every reason to believe that he could pass power down to his heirs. Though many public shareholders may not realize as much, a growing number of tech founders enjoy the kind of dual-class shares that Neumann had extracted from investors, shares that don’t merely give founders more voting power for a while after their companies go public or even throughout their lifetimes, but whose power can be passed down to their children, too.

We wrote about this very issue as a kind of hypothetical last month, quoting SEC Commissioner Robert Jackson, a longtime legal scholar and law professor, who told an audience last year that nearly half of companies that went public with dual-class shares between 2004 and 2018 gave corporate insiders “outsized voting rights in perpetuity.”

Warned Jackson, “Those companies are asking shareholders to trust management’s business judgment — not just for five years, or 10 years, or even 50 years. Forever.” Such perpetual dual-class ownership “asks them to trust that founder’s kids. And their kids’ kids. And their grandkid’s kids . . . It raises the prospect that control over our public companies, and ultimately of Main Street’s retirement savings, will be forever held by a small, elite group of corporate insiders — who will pass that power down to their heirs.”

You might argue that it’s senseless to worry, that the market will speak as it did in WeWork’s case. But not every company has such apparent flaws, and Neumann could have made himself a lot harder to shake than he did. In fact, the broader question the video raises is whether anyone will step in to stop the broader trend, or if public market investors will be living with the consequences down the road instead.

Neumann wasn’t insane to imagine the scenario that he did. That doesn’t mean it’s rational. Giving founders super-voting shares for some period after transitioning onto the public market, we can understand. Giving founders so much power that their kids call the shots of these publicly traded companies? Now that is crazy.

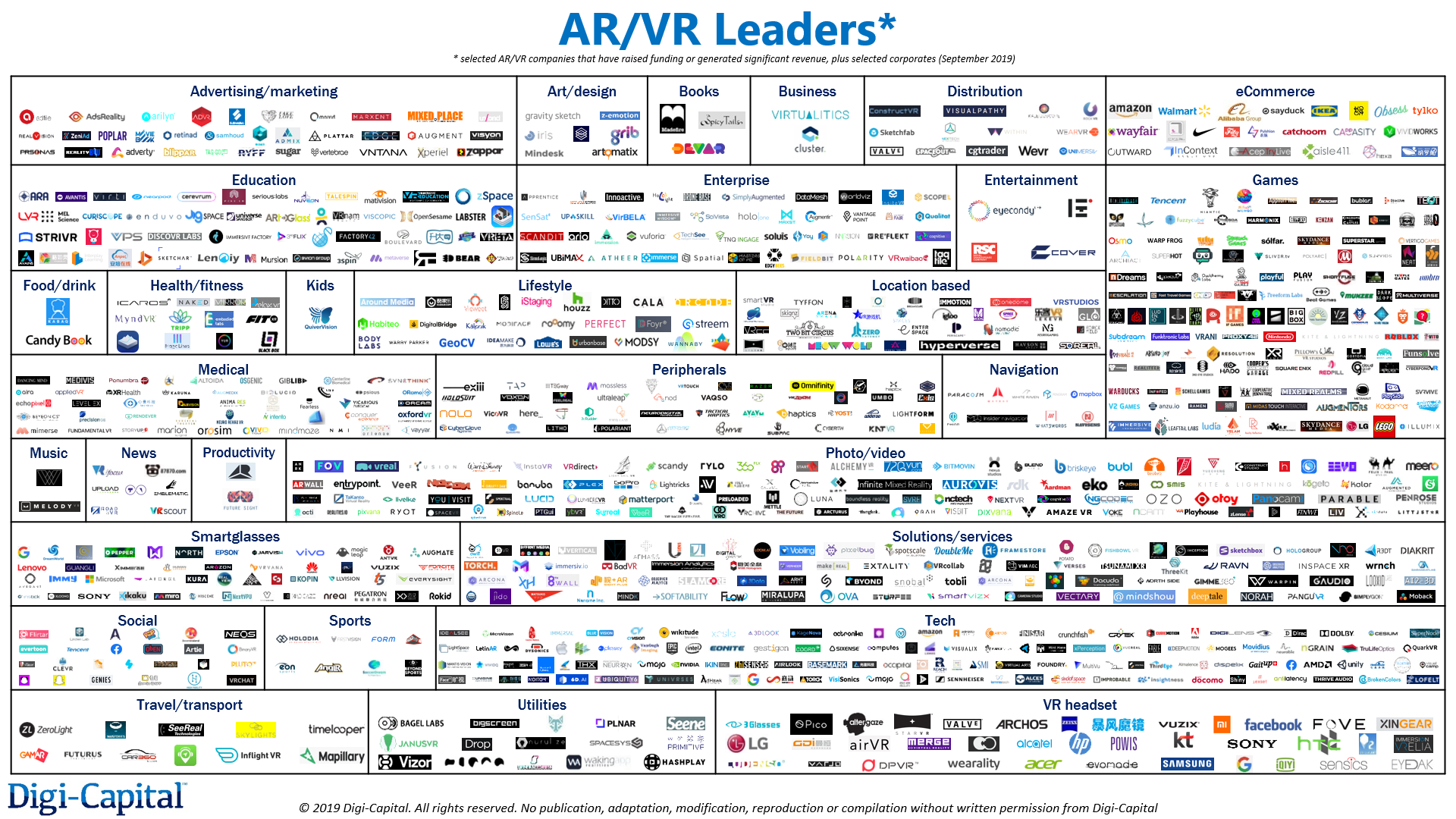

VR/AR startup valuations reach $45 billion (on paper)

Despite early-stage virtual reality market and augmented reality market valuations softening in a transitional period, total global AR/VR startup valuations are now at $45 billion globally — include non-pure play AR/VR startups discussed below, and that amount exceeds $67 billion. More than $8 billion has been returned to investors through M&A already, with the remaining augmented and virtual reality startups carrying more than $36 billion valuations on paper. Only time will tell how much of this value gets realized for investors.

(Note: this analysis is of AR/VR startup valuations only, excluding internal investment by large corporates like Facebook . Again, this analysis is of valuation, not revenue.)

Selected AR/VR companies that have raised funding or generated significant revenue, plus selected corporates as of September 2019.

There is significant value concentration, with just 18 AR/VR pure plays accounting for half of the $45 billion global figure. Some of the large valuations are for Magic Leap (well over $6 billion), Niantic (nearly $4 billion), Oculus ($3 billion from exit to Facebook), Beijing Moviebook Technology ($1 billion+) and Lightricks ($1 billion). While there are unicorns, the market hasn’t seen an AR/VR decacorn yet.

Across all industries — not just AR/VR — around 60% of VC-backed startups fail, not 90% as often quoted. That doesn’t mean this many startups crash and burn, but that 60% of startups deliver less than 1x return on investment (ROI) to investors (i.e. investors get less back than they put in). To better understand what’s happening in AR/VR, let’s analyze the thousands of startup valuations in Digi-Capital’s AR/VR Analytics Platform to see where the smart money is by sector, stage and country.

Tilting Point acquires game monetization startup Gondola

Tilting Point announced yesterday that it has acquired Gondola, a company that aims to increase game monetization by optimizing in-game offers and video ads.

Tilting Point CEO Kevin Segalla described his company’s model as “progressive publishing” — usually, mobile game developers start working with Tilting Point because they need help with user acquisition, and then develop a deeper publishing relationship over time.

“With a select group of our development partners, we’ll acquire an IP, and we’ll … have them take the engine that they already have and create a whole new game,” Segalla said. “It’s really a dual effort between us and the developer.”

To accomplish all this, the company has built artificial intelligence tools to improve user acquisition. But the other side of that equation, in Segalla’s view, is increasing the lifetime value of the users acquired.

“At the end of the day, scaling a game boils down to two simple things, [cost per install] and LTV,” he said. “Strong developers are working to improve the LTV of their players, but there’s a lot of low-hanging fruit that with the right toolset you can use to improve the lifetime values. That’s what Gondola is about … We’ve been following for years, and we said, ‘Let’s bring this in-house.’ ”

Gondola currently offers four modules: Target Optimization (choosing the best offer for a player), Rewarded Video Ad Optimization (choosing the right amount of virtual currency to reward a player for watching a video ad), Store Optimization (choosing the right store items to show a player) and Currency Optimization (choosing the best virtual currency amounts for offers and promotions).

The financial terms of the acquisition — Tilting Point’s first — were not disclosed. As part of the deal, Gondola CTO André Cohen is joining Tilting Point as its head of data science, while his co-founder and CEO Niklas Herriger remains involved as an executive advisor.