Does quantum computing really exist? It’s fitting that for decades this field has been haunted by the fundamental uncertainty of whether it would, eventually, prove to be a wild goose chase. But Google has collapsed this nagging superposition with research not just demonstrating what’s called “quantum supremacy,” but more importantly showing that this also is only the very beginning of what quantum computers will eventually be capable of.

This is by all indications an important point in computing, but it is also very esoteric and technical in many ways. Consider, however, that in the 60s, the decision to build computers with electronic transistors must have seemed rather an esoteric point as well. Yet that was in a way the catalyst for the entire Information Age.

Most of us were not lucky enough to be involved with that decision or to understand why it was important at the time. We are lucky enough to be here now — but understanding takes a bit of explanation. The best place to start is perhaps with computing and physics pioneers Alan Turing and Richard Feynman.

‘Because nature isn’t classical, dammit’

The universal computing machine envisioned by Turing and others of his generation was brought to fruition during and after World War II, progressing from vacuum tubes to hand-built transistors to the densely packed chips we have today. With it evolved an idea of computing that essentially said: If it can be represented by numbers, we can simulate it.

That meant that cloud formation, object recognition, voice synthesis, 3D geometry, complex mathematics — all that and more could, with enough computing power, be accomplished on the standard processor-RAM-storage machines that had become the standard.

But there were exceptions. And although some were obscure things like mathematical paradoxes, it became clear as the field of quantum physics evolved that it may be one of them. It was Feynman who proposed in the early 80s that if you want to simulate a quantum system, you’ll need a quantum system to do it with.

“I’m not happy with all the analyses that go with just the classical theory, because nature isn’t classical, dammit, and if you want to make a simulation of nature, you’d better make it quantum mechanical,” he concluded, in his inimitable way. Classical computers, as he deemed what everyone else just called computers, were insufficient to the task.

Richard Feynman made the right call, it turns out.

The problem? There was no such thing as a quantum computer, and no one had the slightest idea how to build one. But the gauntlet had been thrown, and it was like catnip to theorists and computer scientists, who since then have vied over the idea.

Could it be that with enough ordinary computing power, power on a scale Feynman could hardly imagine — data centers with yottabytes of storage and exaflops of processing — we can in fact simulate nature down to its smallest, spookiest levels?

Or could it be that with some types of problems you hit a wall, and that you can put every computer on Earth to a task and the progress bar will only tick forward a percentage point in a million years, if that?

And, if that’s the case, is it even possible to create a working computer that can solve that problem in a reasonable amount of time?

In order to prove Feynman correct, you would have to answer all of these questions. You’d have to show that there exists a problem that is not merely difficult for ordinary computers, but that is effectively impossible for them to solve even at incredible levels of power. And you would have to not just theorize but create a new computer that not just can but does solve that same problem.

By doing so you would not just prove a theory, you would open up an entirely new class of problem-solving, of theories that can be tested. It would be a moment when an entirely new field of computing first successfully printed “hello world” and was opened up for everyone in the world to use. And that is what the researchers at Google and NASA claim to have accomplished.

In which we skip over how it all actually works

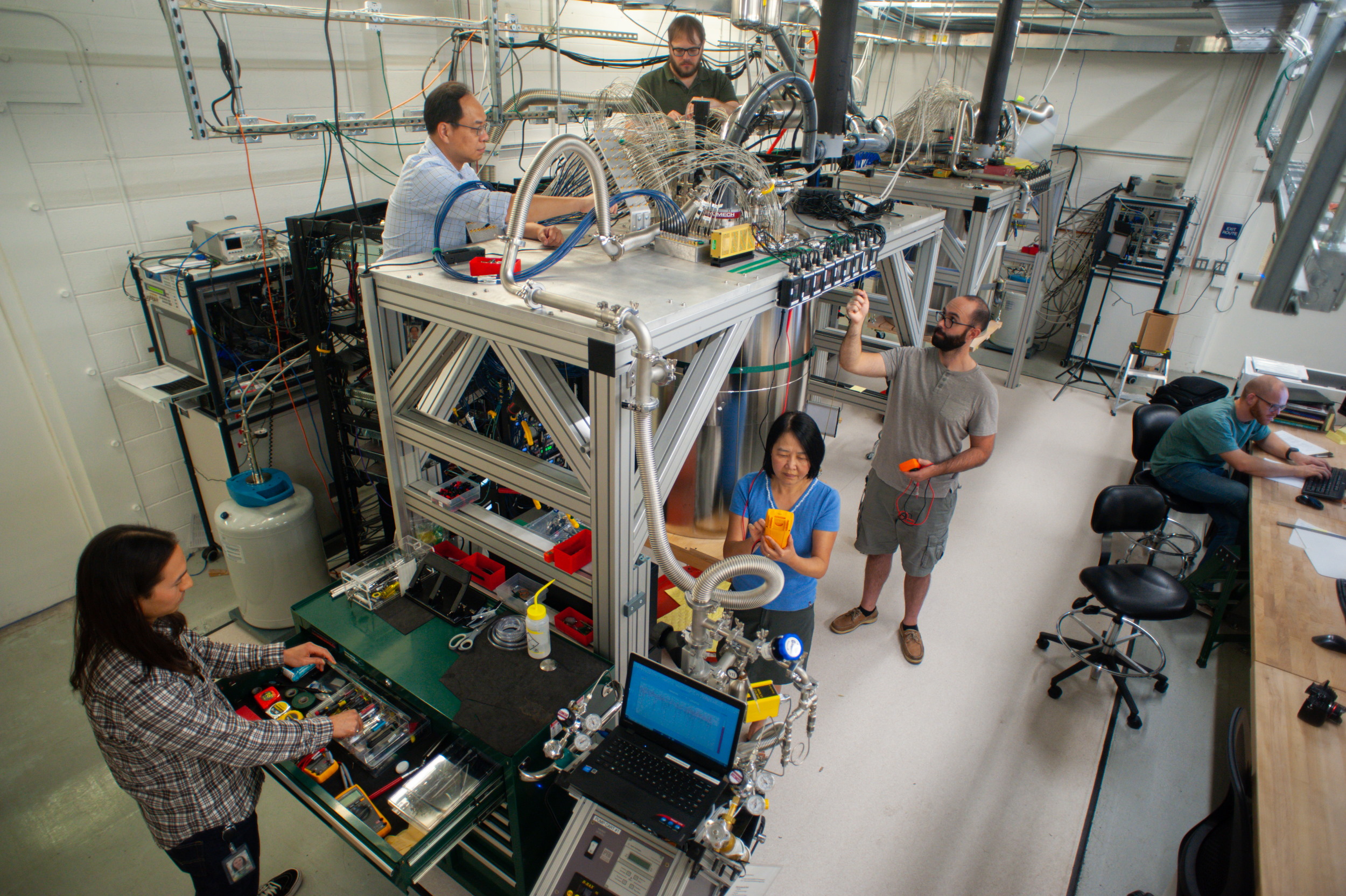

One of the quantum computers in question. I talked with that fellow in the shorts about microwave amps and attenuators for a while.

Much has already been written on how quantum computing differs from traditional computing, and I’ll be publishing another story soon detailing Google’s approach. But some basics bear mentioning here.

Classical computers are built around transistors that, by holding or vacating a charge, signify either a 1 or a 0. By linking these transistors together into more complex formations they can represent data, or transform and combine it through logic gates like AND and NOR. With a complex language specific to digital computers that has evolved for decades, we can make them do all kinds of interesting things.

Quantum computers are actually quite similar in that they have a base unit that they perform logic on to perform various tasks. The difference is that the unit is more complex: a qubit, which represents a much more complex mathematical space than simply 0 or 1. Instead you may think of their state may be thought of as a location on a sphere, a point in 3D space. The logic is also more complicated, but still relatively basic (and helpfully still called gates): That point can be adjusted, flipped, and so on. Yet the qubit when observed is also digital, providing what amounts to either a 0 or 1 value.

By virtue of representing a value in a richer mathematical space, these qubits and manipulations thereof can perform new and interesting tasks, including some which, as Google shows, we had no ability to do before.

A quantum of contrivance

In order to accomplish the tripartite task summarized above, first the team had to find a task that classical computers found difficult but that should be relatively easy for a quantum computer to do. The problem they settled on is in a way laughably contrived: Being a quantum computer.

In a way it makes you want to just stop reading, right? Of course a quantum computer is going to be better at being itself than an ordinary computer will be. But it’s not actually that simple.

Think of a cool old piece of electronics — an Atari 800. Sure, it’s very good at being itself and running its programs and so on. But any modern computer can simulate an Atari 800 so well that it could run those programs in orders of magnitude less time. For that matter, a modern computer can be simulated by a supercomputer in much the same way.

Furthermore, there are already ways of simulating quantum computers — they were developed in tandem with real quantum hardware so performance could be compared to theory. These simulators and the hardware they simulate differ widely, and have been greatly improved in recent years as quantum computing became more than a hobby for major companies and research institutions.

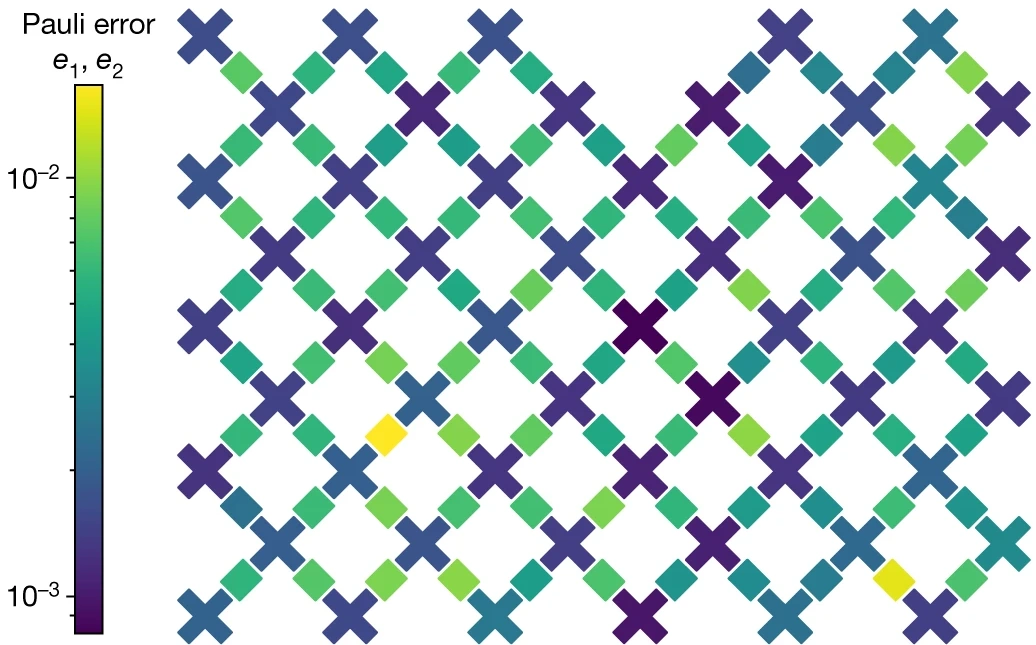

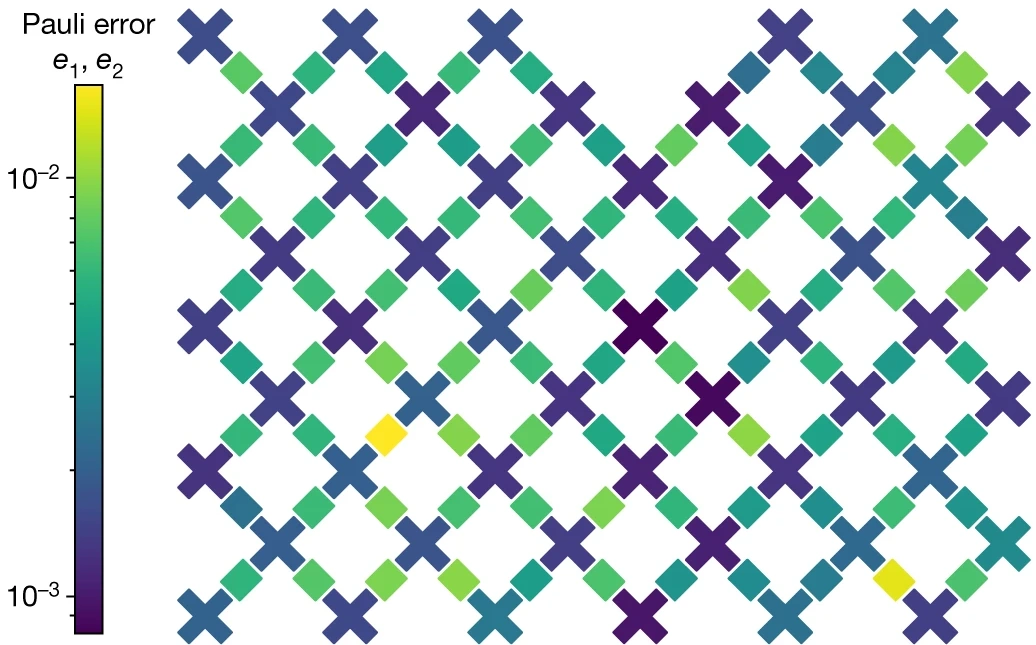

This shows the “lattice” of qubits as they were connected during the experiment (colored by the amount of error they contributed, which you don’t need to know about.)

To be specific, the problem was simulating the output of a random sequence of gates and qubits in a quantum computer. Briefly stated, when a circuit of qubits does something, the result is, like other computers, a sequence of 0s and 1s. If it isn’t calculating something in particular, those numbers will be random — but crucially, they are “random” in a very specific, predictable way.

Think of a pachinko ball falling through its gauntlet of pins, holes and ramps. The path it takes is random in a way, but if you drop 10,000 balls from the exact same position into the exact same maze, there will be patterns in where they come out at the bottom — a spread of probabilities, perhaps more at the center and less at the edges. If you were to simulate that pachinko machine on a computer, you could test whether your simulation is accurate by comparing the output of 10,000 virtual drops with 10,000 real ones.

It’s the same with simulating a quantum computer, though of course rather more complex. Ultimately however the computer is doing the same thing: simulating a physical process and predicting the results. And like the pachinko simulator, its accuracy can be tested by running the real thing and comparing those results.

But just as it is easier to simulate a simple pachinko machine than a complex one, it’s easier to simulate a handful of qubits than a lot of them. After all, qubits are already complex. And when you get into questions of interference, slight errors and which direction they’d go, etc. — there are, in fact, so many factors that Feynman decided at some point you wouldn’t be able to account for them all. And at that point you would have entered the realm where only a quantum computer can do so — the realm of “quantum supremacy.”

Exponential please, and make it a double

After 1,400 words, there’s the phrase everyone else put right in the headline. Why? Because quantum supremacy may sound grand, but it’s only a small part of what was accomplished, and in fact this result in particular may not last forever as an example of having reached those lofty heights. But to continue.

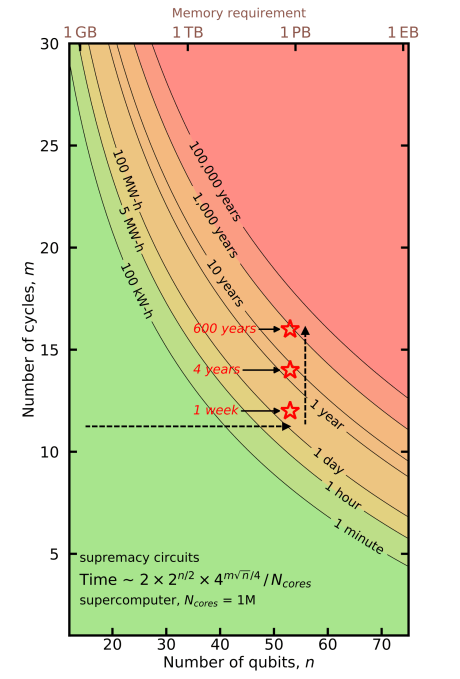

Google’s setup, then, was simple. Set up randomly created circuits of qubits, both in its quantum computer and in the simulator. Start simple with a few qubits doing a handful of operational cycles and compare the time it takes to produce results.

Bear in mind that the simulator is not running on a laptop next to the fridge-sized quantum computer, but on Summit — a supercomputer at Oak Ridge National Lab currently rated as the most powerful single processing system in the world, and not by a little. It has 2.4 million processing cores, a little under 3 petabytes of memory, and hits about 150 petaflops.

At these early stages, the simulator and the quantum computer happily agreed — the numbers they spat out, the probability spreads, were the same, over and over.

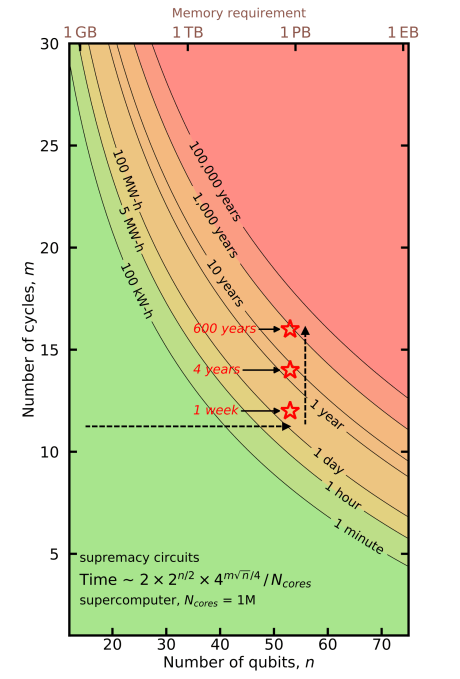

But as more qubits and more complexity got added to the system, the time the simulator took to produce its prediction increased. That’s to be expected, just like a bigger pachinko machine. At first the times for actually executing the calculation and simulating it may have been comparable — a matter of seconds or minutes. But those numbers soon grew hour by hour as they worked their way up to 54 qubits.

When it got to the point where it took the simulator five hours to verify the quantum computer’s result, Google changed its tack. Because more qubits isn’t the only way quantum computing gets more complex (and besides, they couldn’t add any more to their current hardware). Instead, they started performing more rounds of operations with a given circuit, which adds all kinds of complexity to the simulation for a lot of reasons that I couldn’t possibly explain.

For the quantum computer, doing another round of calculations takes a fraction of a second, and even multiplied by thousands of times to get the required number of runs to produce usable probability numbers, it only ended up taking the machine several extra seconds.

You know it’s real because there’s a chart. The dotted line (added by me) is the approximate path the team took, first adding qubits (x-axis) and then complexity (y-axis).

For the simulator, verifying these results took a week — a week, on the most powerful computer in the world.

At that point the team had to stop doing the actual simulator testing, since it was so time-consuming and expensive. Yet even so, no one really claimed that they had achieved “quantum supremacy.” After all, it may have taken the biggest classical computer ever created thousands of times longer, but it was still getting done.

So they cranked the dial up another couple notches. 54 qubits, doing 25 cycles, took Google’s Sycamore system 200 seconds. Extrapolating from its earlier results, the team estimated that it would take Summit 10,000 years.

What happened is what the team called double exponential increase. It turns out that adding qubits and cycles to a quantum computer adds a few microseconds or seconds every time — a linear increase. But every qubit you add to a simulated system makes that simulation exponentially more costly to run, and it’s the same story with cycles.

Imagine if you had to do whatever number of push-ups I did, squared, then squared again. If I did 1, you would do 1. If I did 2, you’d do 16. So far no problem. But by the time I get to 10, I’d be waiting for weeks while you finish your 10,000 push-ups. It’s not exactly analogous to Sycamore and Summit, since adding qubits and cycles had different and varying exponential difficulty increases, but you get the idea. At some point you can have to call it. And Google called it when the most powerful computer in the world would still be working on something when in all likelihood this planet will be a smoking ruin.

It’s worth mentioning here that this result does in a way depend on the current state of supercomputers and simulation techniques, which could very well improve. In fact IBM published a paper just before Google’s announcement suggesting that theoretically it could reduce the time necessary for the task described significantly. But it seems unlikely that they’re going to improve by multiple orders of magnitude and threaten quantum supremacy again. After all, if you add a few more qubits or cycles, it gets multiple orders of magnitude harder again. Even so, advances on the classical front are both welcome and necessary for further quantum development.

‘Sputnik didn’t do much, either’

So the quantum computer beat the classical one soundly on the most contrived, lopsided task imaginable, like pitting an apple versus an orange in a “best citrus” competition. So what?

Well, as founder of Google’s Quantum AI lab Hartmut Neven pointed out, “Sputnik didn’t do much either. It just circled the Earth and beeped.” And yet we always talk about an industry having its “Sputnik moment” — because that was when something went from theory to reality, and began the long march from reality to banality.

The ritual passing of the quantum computing core.

That seemed to be the attitude of the others on the team I talked with at Google’s quantum computing ground zero near Santa Barbara. Quantum superiority is nice, they said, but it’s what they learned in the process that mattered, by confirming that what they were doing wasn’t pointless.

Basically it’s possible that a result like theirs could be achieved whether or not quantum computing really has a future. Pointing to one of the dozens of nearly incomprehensible graphs and diagrams I was treated to that day, hardware lead and longtime quantum theorist John Martines explained one crucial result: The quantum computer wasn’t doing anything weird and unexpected.

This is very important when doing something completely new. It was entirely possible that in the process of connecting dozens of qubits and forcing them to dance to the tune of the control systems, flipping, entangling, disengaging, and so on — well, something might happen.

Maybe it would turn out that systems with more than 14 entangled qubits in the circuit produce a large amount of interference that breaks the operation. Maybe some unknown force would cause sequential qubit photons to affect one another. Maybe sequential gates of certain types would cause the qubit to decohere and break the circuit. It’s these unknown unknowns that have caused so much doubt over whether, as asked at the beginning, quantum computing really exists as anything more than a parlor trick.

Imagine if they discovered that in digital computers, if you linked too many transistors together, they all spontaneously lost their charge and went to 0. That would put a huge limitation on what a transistor-based digital computer was capable of doing. Until now, no one knew if such a limitation existed for quantum computers.

“There’s no new physics out there that will cause this to fail. That’s a big takeaway,” said Martines. “We see the same errors whether we have a simple circuit or complex one, meaning the errors are not dependent on computational complexity or entanglement — which means the complex quantum computing going on doesn’t have fragility to it because you’re doing a complex computation.”

They operated a quantum computer at complexities higher than ever before, and nothing weird happens. And based on their observations and tests, they found that there’s no reason to believe they can’t take this same scheme up to, say, a thousand qubits and even greater complexity.

Hello world

That is the true accomplishment of the work the research team did. They found out, in the process of achieving the rather overhyped milestone of quantum superiority, that quantum computers are something that can continue to get better and to achieve more than simply an interesting experimental results.

This was by no means a given — like everything else in the world, quantum or classical, it’s all theoretical until you test it.

It means that sometime soonish, though no one can really say when, quantum computers will be something people will use to accomplish real tasks. From here on out, it’s a matter of getting better, not proving the possibility; of writing code, not theorizing whether code can be executed.

It’s going from Feynman’s proposal that a quantum computer will be needed to using a quantum computer for whatever you need it for. It’s the “hello world” moment for quantum computing.

Feynman, by the way, would probably not be surprised. He knew he was right.

Google’s paper describing their work was published in the journal Nature. You can read it here.