Contributor

The Royal Air Force delayed safety warnings about the first transatlantic flight of a new Reaper aircraft in 2018, over fears that they could tip anti-drone protestors to its arrival in the U.K., according to emails seen by TechCrunch.

On July 11, 2018, the General Atomics SkyGuardian, a variant of the U.S. Reaper drone that killed Iranian military leader Qasem Soleimani in January, flew from Grand Forks, N.D., to RAF Fairford in Gloucestershire. This was the first and only time that a drone had made such a journey through U.K. civilian airspace, and it paved the way for an even more ambitious test due to happen in the U.S. later this month.

The 5.5-metric ton aircraft was remotely piloted throughout its 24-hour journey using satellite communications to relay video, instrument data and air traffic control instructions to pilots at General Atomics’ airbase in North Dakota.

The historic flight, which passed directly over Hereford and Gloucester, concluded without incident at RAF Fairford, where the drone went on static display during the Royal International Air Tattoo, a military air show.

General Atomics chief executive Linden Blue said: “The successful flight of the [SkyGuardian] is the culmination of the hard work and innovation of our dedicated employees, and the strong relationships that we enjoy with the RAF, the U.K. Civil Aviation Authority (CAA), the Royal International Air Tattoo and our U.K. industry partners.”

However, emails obtained under U.K. Freedom of Information legislation, and first reported by The Guardian, show that those relationships were tenuous at best, with the CAA distrusting General Atomics, questioning the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration’s oversight of the SkyGuardian and facing sustained pressure from the Ministry of Defence to delay safety measures.

The CAA, the U.K.’s aviation regulator, supplied more than 1,600 pages of emails regarding the flight. All were heavily redacted, including most names and job titles.

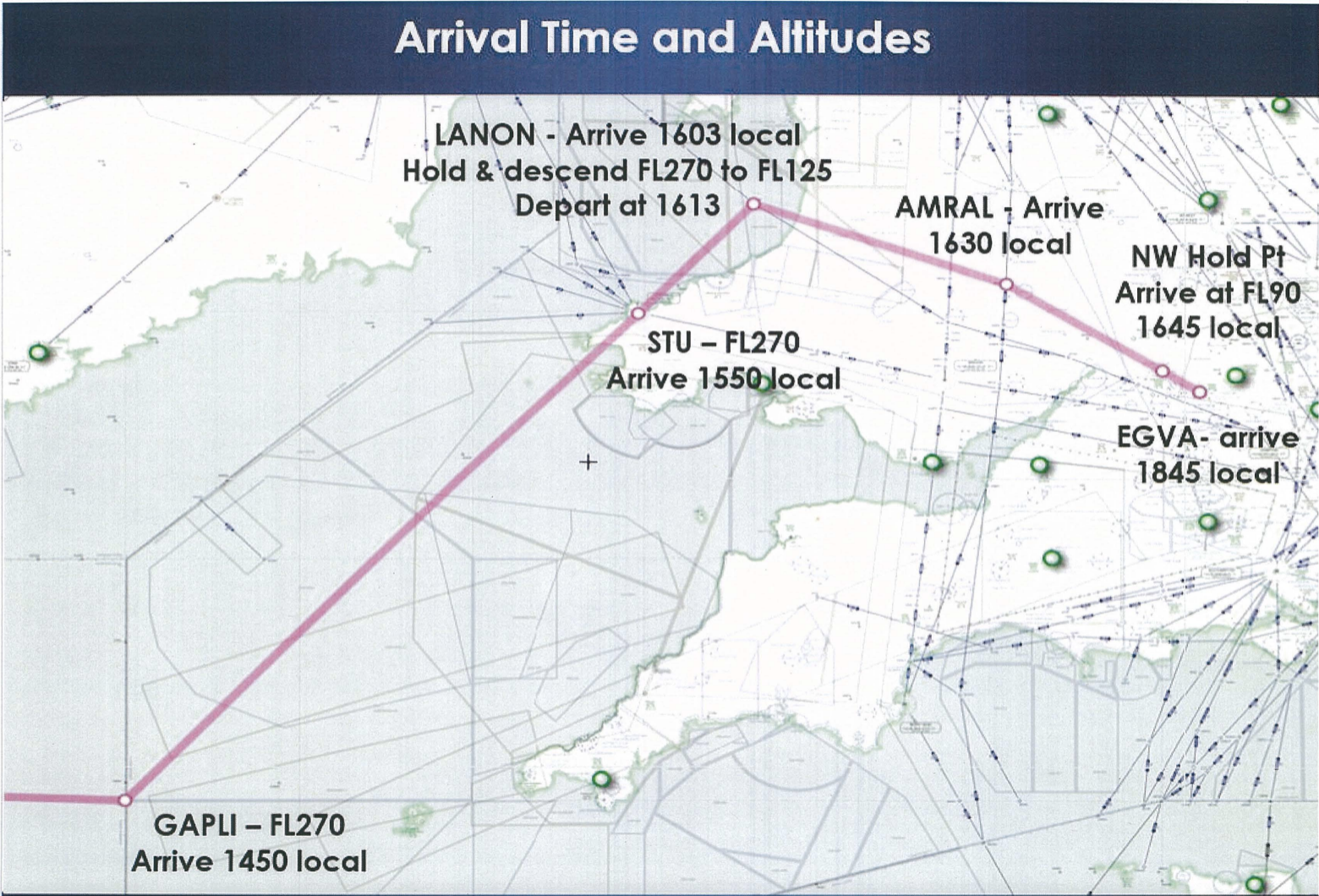

Plan for the final leg of the SkyGuardian’s transatlantic flight, travelling between Ireland and England, then flying over Wales to land at Fairford airbase (Credit: General Atomics/CAA)

It is unclear who first suggested a high-profile transatlantic Reaper flight to mark the RAF’s centenary and showcase the new drone at the Air Tattoo. But by early February, the CAA was already warning of pressure from the military to allow the flight.

“We will need to be fully satisfied that the flight can be conducted in a safe manner before we will approve this,” wrote a CAA manager to Mark Swan, then the regulator’s director of Safety. “Note that there is likely to be extensive interest from MoD sources… and hence some higher level pressure focussed on the CAA for this flight to take place.”

That is because the RAF is in the process of procuring 20 next-generation Reaper drones from General Atomics in a deal worth more than £1.1 billion (US$1.4 billion). These drones, which the RAF will call Protector, are a military version of the SkyGuardian that undertook the transatlantic flight.

The RAF already has 10 Reaper drones, a larger and more heavily armed variant of the Predator. Since 2008, these have been used to carry out hundreds of deadly strikes in Afghanistan, Iraq and Syria. While these drones are remotely controlled by RAF pilots in Nevada and Lincolnshire, the Reapers are not allowed to share civilian airspace with passenger jets. This means that they have to be based very near to where they operate — an expensive and limiting requirement.

A drone like the SkyGuardian that could fly amid commercial aircraft for many thousands of miles would enable the RAF to attack targets across much of the world from the bases in Britain. “A drone that can fly in a civilian airspace is so much more versatile,” says Arthur Holland Michel, co-director of the Center for the Study of the Drone at Bard College in New York.

When the Protector drones enter service in the U.K. in 2024, they will carry two British-made weapons: a GPS- and laser-guided bomb called the Paveway IV; and a semi-autonomous missile called Brimstone. Although the transatlantic drone would be unarmed, the RAF saw it as a potentially lucrative sales demonstration for other countries.

“The eyes of a number of potential customer nations such as [Australia] and [Canada] will be on the event and the outcome could be significant for UK prosperity,” wrote the RAF’s program manager for Protector in an internal email to the MoD.

The CAA was skeptical from the outset. “The general impression of General Atomics… is that they will try to ‘push the limits’ and over promise in many areas,” wrote a safety official in March. “We need to tread really carefully on this one – the fact that MoD is involved is not a reason for us to roll over and just let this happen.”

The regulator’s concerns were simple. How would the aircraft know where it was? How would pilots thousands of miles away know what was happening around the drone? And how could they ensure they had control of it at all times?

The CAA has an exhaustive procedure for assessing the safety of aircraft, and another long list of requirements for allowing drones to take to the skies above Britain. There was no way that the SkyGuardian could be properly tested by the U.K. regulator in a few short months before the planned flight in July.

Instead, General Atomics could apply for an overflight exemption — permission for a single flight on a given day. This exemption would rely on another credible organisation attesting to the airworthiness of the aircraft, in this case, the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration (FAA).

The problem was that the FAA had itself placed severe limits on how and where the SkyGuardian could operate. It usually required the SkyGuardian to have a visual observer spotting for the drone from a nearby chase plane whenever it was below 18,000 feet. The FAA also banned the drone from flying over most densely populated areas.

“I do not really see how such limitations would… allow the aircraft to commence the first part of its flight out of the United States, let alone over Canada and then into the oceanic system,” wrote a CAA safety official to General Atomics. “The limitation regarding overflight of densely populated areas… will bring in additional problems within the UK (which is already quite densely populated).”

For its part, the FAA insisted that its authority finished at the edge of American airspace. “Whether manned or unmanned, [we] cannot provide any sort of safety statement that would ensure safe operations in UK airspace,” wrote an FAA official to the CAA in March.

“If General Atomics can’t get the FAA to back up the safety of the aircraft, then why should we be letting it into our airspace?,” wondered one CAA official.

It seemed as though the same thought had occurred to authorities in Ireland. The shortest route for many transatlantic flights between the U.S. and the U.K. is directly across Ireland. However, a track of the SkyGuardian’s route shows a distinct kink to keep the drone out over the Atlantic and the Irish Sea.

In April, a CAA airspace official reported a phone call with their counterpart at the Irish Aviation Authority: “I explained why the decision was made to route south of Irish landmass… However, due to how the Irish will be segregating the airspace and in addition to the commercial traffic routing across the Atlantic, they have requested that [SkyGuardian] now routes [even] further south.”

In aviation, segregation is when an aircraft does not fly in close proximity to other planes but instead has a corridor carved out for its sole use. Although General Atomics’ ultimate aim is for the SkyGuardian (and the RAF’s Protector) to use advanced sensors to autonomously detect and avoid hazards, the entire transatlantic flight would take place in segregated airspace, at least several miles from other aircraft.

Even so, the FAA would have had to adjust the SkyGuardian’s domestic certification to allow it to fly over cities, and without a chase plane. “In its current format and limitations there is not a lot the CAA can do with this,” wrote a CAA official. “We need to sit down and discuss this, as there are political forces at play here and [we are] getting a lot of pressure from the MoD.”

Eventually, the FAA relented, relaxing the SkyGuardian’s restrictions for the transatlantic flight. It does not appear that the CAA had any say in setting those conditions, which were redacted in the CAA emails. However, the drone flew directly over the city of Gloucester and did not have a chase plane.

Following a meeting about the proposed flight in early June, one CAA official reported that the regulator was “simply taking the FAA’s experimental certification and ‘anglicising’ it.”

Now that the flight seemed as if it would actually happen, attention within the RAF and CAA shifted to public relations.

Although the SkyGuardian would be displayed at the Air Tattoo with British bombs and missiles, the RAF wanted the flight and SkyGuardian to sound as innocuous as possible. RAF High Command edited an article intended for the defence publication Jane’s to remove references to the SkyGuardian’s large weapons load and its ability to “greatly [compress] the sensor to shooter kill-chain between detection and an armed response.”

“I have cut out the weapons bit as this detracts from the article and moves focus from the achievement of the flight to how easily we can kill people,” wrote an RAF officer. The same officer also added a paragraph about how the SkyGuardian could provide humanitarian assistance, disaster relief, coastal surveys, search and rescue and even monitor flood defences.

“This is all part of the narrative that [remote piloted aircraft] are a good thing and I am keen to keep the wind out of the anti-drone lobby sails,” he wrote.

General Atomics was now excited to announce the upcoming flight as quickly as possible. But on June 11, a CAA official noted that a press release from General Atomics had been blocked by the MoD “due to concerns about the potential for “anti (military) drone” protests hampering the arrival at Fairford if the flight is publicised too early.”

A week later, the MoD suggested that the CAA only announce the 4,300-mile transatlantic crossing just six days before the flight itself.

“We have significant concerns this is too late,” complained a CAA official to Mark Swan, its head of safety. “[We] endeavour to provide at least 60 days’ notification of large airspace restrictions to notify other airspace users… The longer we leave to notify, the higher the risk of airspace infringements.”

A particular worry was a British Gliding Association competition scheduled to take place just 10 miles from the SkyGuardian’s airspace on the day of its flight. If one of the gliders should stray into the drone’s path, it could risk a catastrophic collision.

“Sadly, I have had a huge kickback from the RAF regarding going public,” wrote another CAA official. “I have been informed that the RAF [is trying to] delay this as long as possible…. Patience is running thin thanks to the MoD.”

Ultimately, the CAA disregarded the military’s concerns, and issued its airspace warning at the end of June. Only one decision was left to be made: What should the SkyGuardian be called?

One CAA airspace expert suggested calling it nothing at all, with the warning vaguely referencing “a civilian aircraft, certificated and registered through the FAA… to mitigate the risk of anti-drones protests for [the] MoD.”

Another CAA official agreed that the word “drone” should be avoided wherever possible. “[We can] refer to it as either an Unmanned Aircraft or as a Remotely Piloted Aircraft… I believe the terminology of ‘drone’ does not fit this aircraft for a number of reasons.”

RAF High Command concurred, with an RAF officer writing: “It is clear from our teamwork that we are all consistent and clear on each other’s priorities moving forward, particularly with the incorrect use of ‘drone’.”

Experimental SkyGuardian drone flying over the UK on the first ever transatlantic drone flight through civilian airspace (Credit: General Atomics)

At last, the CAA and the RAF could agree on something. Whatever flew uncrewed from America to Britain, with its remote pilot, satellite control and ability to carry multiple precision-guided weapons, it certainly wasn’t a drone.

The flight itself went pretty much to plan. The SkyGuardian took off from Grand Forks just after midday on 10 July, and flew through the night at 27,000 feet over Canada and the North Atlantic on a meticulously charted route. Pilots in North Dakota, controlling the SkyGuardian in shifts, connected with U.S., Canadian, Irish and British air traffic controllers.

Arriving off the coast of Wales, the SkyGuardian descended into a holding pattern above Cirencester before coming in to land at Fairford, using an automated landing system. There were no anti-drone protestors waiting to greet it.

After the Tattoo was over, the SkyGuardian was dismantled and flown back to the U.S. as cargo, its mission complete.

In January 2019, General Atomics announced that defense contractor BAE Systems was developing a plan for regular RAF Protector operations in U.K. civilian airspace. In November, the Australian government announced that it would spend $1.3 billion Australian dollars (£670 million) to acquire a fleet of SkyGuardians as its next unmanned aerial vehicle. Canada and Greece are also reported to be considering purchasing the aircraft.

But the jewel in the crown for General Atomics is the U.S. market. On March 23, a SkyGuardian equipped with an experimental autonomous detect-and-avoid system and a cutting-edge surveillance radar will take to the skies above Southern California, fully integrated with normal air traffic control for the first time. According to a filing with the FCC, it will fly for over 100 miles, conducting aerial inspection and surveillance of “critical infrastructure owned by commercial and civil entities.”

“This type of commercial mission has never been done with a [drone] anywhere in the United States,” wrote General Atomics. “It is a first of its kind and will serve as a proof of concept for future… missions.”

If the test goes well, military and commercial Reapers and SkyGuardians could soon start flying over U.S. cities, either on their way to foreign war zones, or with their tireless digital eyes gathering data on America itself.