Where are you? That’s not just a metaphysical question, but increasingly a geopolitical challenge that is putting tech giants like Apple and Alphabet in a tough position.

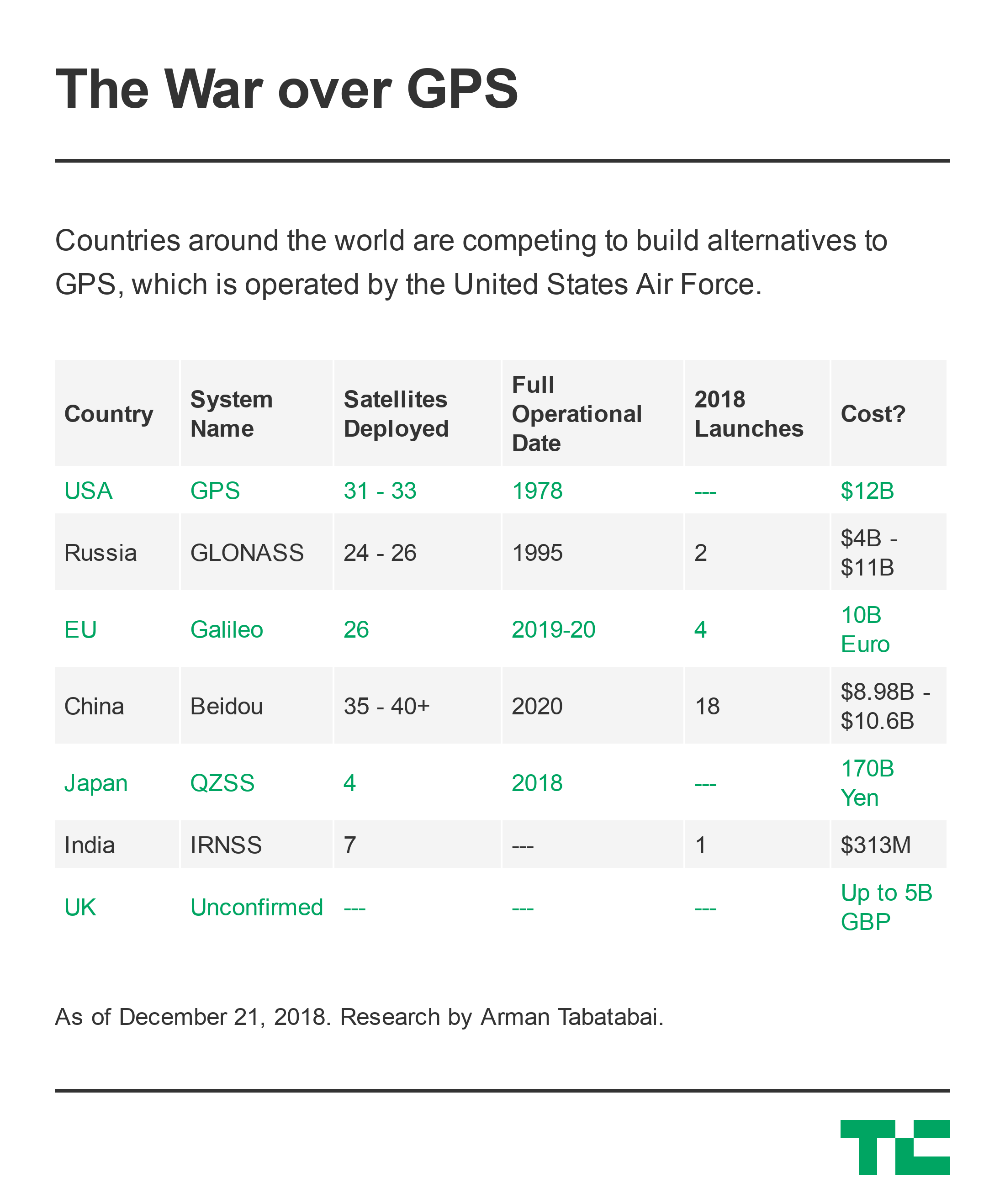

Countries around the world, including China, Japan, India and the United Kingdom plus the European Union are exploring, testing and deploying satellites to build out their own positioning capabilities.

That’s a massive change for the United States, which for decades has had a practical monopoly on determining the location of objects through its Global Positioning System (GPS), a military service of the Air Force built during the Cold War that has allowed commercial uses since mid-2000 (for a short history of GPS, check out this article, or for the comprehensive history, here’s the book-length treatment).

Owning GPS has a number of advantages, but the first and most important is that global military and commercial users depend on this service of the U.S. government, putting location targeting ultimately at the mercy of the Pentagon. The development of the technology and the deployment of positioning satellites also provides a spillover advantage for the space industry.

Today, the only global alternative to that system is Russia’s GLONASS, which reached full global coverage a couple of years ago following an aggressive program by Russian president Vladimir Putin to rebuild it after it had degraded following the break-up of the Soviet Union.

Now, a number of other countries want to reduce their dependency on the U.S. and get those economic benefits. Perhaps no where is that more obvious than with China, which has made building out a global alternative to GPS a top national priority. Its Beidou (?? – “Big Dipper”) navigation system has been slowly building up since 2000, mostly focused on providing service in Asia.

Now, though, China hopes to accelerate the launch of Beidou satellites and provide worldwide positioning services. As Financial Times noted a few weeks ago, China has launched 11 satellites in the Beidou constellation just this year — almost half of the entire network, and it hopes to expand by another dozen satellites by 2020. That would make it one of the largest systems in the world when fully deployed.

A Long March-3B carrier rocket carrying the 24th and 25th Beidou navigation satellites takes off from the Xichang Satellite Launch Center on November 5, 2017 in Xichang, China. Photo by Wang Yulei/CHINA NEWS SERVICE/VCG via Getty Images

China is not just putting satellites into orbit though, but demanding that local smartphone manufacturers include Beidou positioning chips in their devices. Today, devices from a number of major manufacturers, including Huawei and Xiaomi, use the system, along with GPS and Russia’s GLONASS as well.

That puts American smartphone leaders like Alphabet and particularly Apple in a bind. For Apple, which prides itself on providing one unified iPhone device worldwide, the disintegration of the monopoly around GPS presents a quandary: Does it offer a unique device for the Chinese market capable of handling Beidou, or does it add Beidou chips to its phones worldwide and run into trouble with U.S. national security authorities?

The complexity doesn’t stop there. China may be the most aggressive in launching its alternative to GPS and also the most bullish in providing worldwide coverage, but it is not alone in pursuing its own system.

Japan has made launching a space program a national priority to compete with China and rejuvenate its economy, and one critical component of that program is building out a positioning system. The Quasi-Zenith Satellite System (?????????), which has cost ¥120 billion ($1.08 billion) to date, is designed to augment GPS with more coverage of Japan and also trigger an estimated ¥2.4 trillion ($21.58 billion) in economic benefits.

Using this new system comes at a huge cost due to lack of manufacturing scale. As the Nikkei Asian Review noted a few weeks ago, “The high price of receivers is a hurdle, however. Mitsubishi Electric on Thursday began selling receivers accurate to within a few centimeters — at a price of several million yen, or tens of thousands of dollars, apiece.” The additional location accuracy in Japan may well be necessary for autonomous cars, but auto manufactures will need to lower costs quickly if they want to include the technology in their vehicles.

Like Japan, India has similarly pursued a GPS-augmenting system known as IRNSS, and it has now launched seven satellites to increase coverage of the subcontinent. Meanwhile, the United Kingdom, which is expected to leave the European Union in March following the referendum over Brexit, will most likely lose access to the EU’s Galileo positioning system, and is planning to launch its own. As for Galileo itself, it is expected to be fully operational in 2019.

In short, the world has moved from one system (GPS) to arguably seven. And while Chinese manufacturers increasingly have GPS, GLONASS and Beidou installed on one chip, that scale may only work in a country the size of China. In Japan, where the smartphone market is saturated and the population is less than a tenth of China, the scale required to lower prices may well be harder to find. It will be even tougher in the United Kingdom, for the same reasons.

Theoretically, one positioning chip could be designed to incorporate all of these different systems, but that might run afoul of U.S. national security laws, particularly in regards to GLONASS and Beidou. Which means that much as the internet is fragmenting into disparate poles, we might soon find that our smartphone positioning chips need to fragment as well in order to handle these local markets. That will ultimately mean higher prices for consumers, and tougher supply chains for manufacturers.