Contributor

Below are excerpts from the most recent episode of the Flux podcast hosted by RRE Ventures principal Alice Lloyd George.

AMLG: Welcome back to the pod. I’m excited to be here with Dr. Assaf Glazer. He is the co-founder and CEO of Nanit a leading human analytics company that uses computer vision to help parents navigate their child’s sleep.

Essentially it’s a baby data collector that every sleep-deprived geek parent has dreamed of. A little background on Assaf: He got his Ph.D. at the Technion in Israel and was previously at Applied Materials as well as Wales where he worked on solutions for missile defense systems. Nanit was born here in New York at Cornell Tech [disclosure?—?RRE is a long-standing investor in the company.] Welcome Assaf it’s great to have you.

AG: Thank you for having me.

AMLG: I’ve got a stat here, that on average parents lose 44 days of sleep during the first year of their baby’s life and nearly 3 in 10 babies have problems sleeping at night. Those numbers sum up the nature of what you’re trying to solve, but can you lay out how you identified this problem and started the company?

AG: It started for me as a parent. You have your baby, you arrive home and you see that your life has changed. Pretty quickly you understand what your number one concern is?—?sleep. You’re tired, you’re sleep deprived. You wake up during the night and do everything necessary to go back to sleep. You’re going to Google and going to friends. This is where Nanit comes in. We are giving you the information that will allow you to make better decisions for your child. Six years ago I had my first child, Udi. He was born when I was at the Technion. I’m a computer vision guy. Before I was at the Technion I worked at Applied Materials in the semiconductor industry, on a camera that you put above the silicon slices, to see them from a bird’s eye perspective.

AMLG: So you were doing computer vision for chip manufacturing?—?on the assembly lines, you’d look for errors in the chips?

AG: Yes. And when my son was born I said, OK let’s do process control for my baby.

AMLG: As if the baby was on an assembly line like a chip, just run some computer vision on it.

AG: Yeah. So I wrote a paper on background subtraction algorithms?—?how to find a foreground object differentiated from the background?—?and applied those algorithms to my baby. I went to my advisors at the Technion and told them, you know, I’ve found that my baby is moving 134 times on average at night. But what can you do with that? I was looking at this data and I said sleep, sleep is what we need to solve here. I went to sleeping labs to try to understand sleep science. Then I moved as a postdoc to Cornell University where I joined the Runway Program, which aims to commercialize science.

The Jacobs institute is a joint venture between Cornell and the Technion-Israel Institute of Technology, operating as an independent entity within Cornell Tech. The Institute emphasizes a trans-disciplinary view of science and encourages translational research to serves the common good, through a set of industry-focused “hubs” that address contemporary needs.

AMLG: So you moved from Israel.

AG: I moved from Israel to where the customers are, which is New York.

AMLG: We also have the most anxious parents on the planet.

AG: Haha yes. I would say that New York is very inspiring. In terms of the culture, the diversity, it’s a great place to be.

AMLG: Tell me about the program at Cornell.

AG: It’s a joint venture for Cornell and Technion University. We were six postdocs that started in this program. They really helped me. Peretz Lavie the president of the Technion, he’s a sleep expert, a sleep guru I would say. He helped us reach out to experts around the world in sleep development and cognitive development. Then we developed Nanit with them.

Dr Peretz Lavie is a world-renowned sleep expert and has been President of the Technion since 2009. Watch his interview on sleep research here.

AG: The development of infant sleep is fascinating. How we move between stages. How to differentiate between awake, asleep, deep sleep, REM sleep.

AMLG: Do babies have deep sleep and REM sleep as well?

AG: When they are born it’s a bit of a mix. They have two states, awake and asleep. And over time?—

AMLG: Like an on off switch.

AG: Haha it’s a bit more, but I’m not sure that we fully understand all the processes during the first few weeks. They dream much more than adults. And you see their architecture developing. One of the first experts that I worked with is Professor Avi Sadeh. I reached out to him through Peretz Lavie, as he developed the gold standard of how to measure sleep. The hypothesis is that movement is an indication of asleep and awake states, and with a camera you know much more. You draw the silhouette of the baby, you can detect the eyes. You can track the different parts of the body and you have better resolution. Today we measure sleep better than the state of the art medical devices. When you do it with a camera it’s powerful because you can capture a lot of things around the sleep architecture. You build a picture. In our case we track the parent. When you look at this behavior?—?sleep and parent intervention patterns?—?you can give tips and recommendations for parents on how to improve, how to teach their baby to sleep on its own.

AMLG: As your user base gets bigger you’re going to have a lot of anonymized metadata that will give you insights—such as the more times you interrupt the baby’s sleep or the more times you leave it alone, this is the effect. So is it the parent-child insights that you’re looking to get?

AG: If you look at studies on sleep, we’re talking about hundreds top. With Nanit you are exposed to thousands of babies sleeping in their natural environment. By looking at their behavior over time we learn new things. Sleep training is awareness and education. You’re building awareness with the data and the videos. We give parents information about how their week was in comparison to other babies of that age. There are no secrets?—?if you have the data you can use triggers to give tips to parents. For instance, I saw that your baby is capable of putting himself back to sleep during the night. Why don’t you wait one or two minutes before you enter the room.

AMLG: On the hardware side, can you share the journey there. You used to do manufacturing in the U.S. and you’ve moved that to China. What have you learned?—?how have margins improved? How did you scale up volume? What are your learnings about manufacturing?

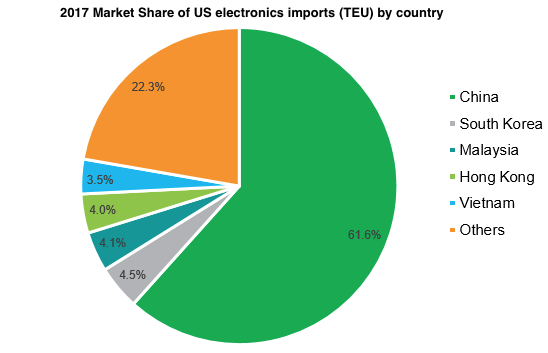

China continues to dominate U.S. electronics imports. Source: IHS Mark

AG: I’ll try to make it short. It’s really hard to build mass production lines in the U.S. for commodity consumer goods. From a labor perspective, prices in the U.S. are high. Over time it won’t exist in the U.S. as there is strong competition from China. But because it is a consumer product, having your designer, engineers and even the line close to you geographically is much more convenient. If you’re looking at the U.S. market, the engineers are also parents, which helps you explain the value proposition of your product. It’s important that even the engineer who designs the circuit board understands what it means to have an LED that is strong enough above the bed. In general every engineer needs to have the product in mind when he does the design. Once we reached a stage that we had a line in the right yield and capacity, we did the transition to China. But it is expensive to work in this way, to start in the U.S. then move to China. There is no one recipe. Nanit also has an R&D center in Israel. Which means that now I’m working in three time zones. It is crazy. Most of our R&D is on the software side and on the hardware side we try to outsource when possible. If I had to choose I would choose Israel and the U.S.

AMLG: How have you found pulling those resources together and acquiring talent. You’ve obviously got a strategic advantage with the connection to Israel, but any insights on how you attract and retain the top talent, especially in machine learning?

AG: Finding the right talent for your company is a search problem. The world is big and in different parts of the world there are different types of talent. In Israel there is great talent for backend engineers and computer vision, and we hire those people in Israel. In the U.S. there’s great talent in marketing, sales, business development, brand development, human centric design?—?for those, New York is a great place to be. In China you find talent related to manufacturing and they are very good at it. In the past it was hard to build a company in this way. But the world changed. The world changed in the sense of how we communicate. The only thing that hasn’t been solved yet is time zones. If everyone slept at the same time that would help. But besides the time zones, technology today can solve a lot of problems. Nanit couldn’t exist a couple of years ago when we didn’t have this.

AMLG: Right you wouldn’t have been able to do it all in Israel or all in New York or all in China. What about on the machine learning side?—?what is going on on a more macro level there?

AG: Deep learning and convolutional neural networks are amazing tools that help us do things we weren’t able to do before. Thanks to deep learning, today I can tell you the baby’s position in the crib better than the human eye. But what happened is that it was so disruptive that many other parts of the computer vision field, you started seeing them less and less at conferences. Add to this the fact that it generates lots of value for companies like Google, Amazon, Microsoft?—

AMLG: So machine learning has become dominated by big platforms like Google and Apple, and perhaps research for research’s sake is a valuable thing and not just having it all steered towards revenue or commercial applications. You’re saying it’s important to have pure research?

AG: This is what research is about. It should be pure.

AMLG: Do you know Gary Marcus? He came on this podcast last year, and his point about these companies is that when you’re a hammer everything looks like a nail. When you have a ton of data?—?you’re Google or Facebook?—?everything looks like you should apply deep learning to it. But that’s their bias and perhaps it skews out other approaches to machine learning.

AG: Also I would say it becomes a commodity over time. I believe the next innovation will be around behavioral analysis, which is the next level of computer vision. We are working on research collaborations that study small twitches of a baby, which could be an indicator of neurological disorders. There is a next level of behavioral neuroscience, it’s a fascinating field that is going to develop over the next couple of years.

AMLG: So you have this background in Israeli defense where you worked on missile defense systems. Can you share anything about that or how it’s informed what you’re doing now? Working in that environment is quite different than having a startup in New York.

AG: I was in a foundational team in the Nineties for a new defense system. It took me a couple of years to understand that I was a beta tester. They used me to understand the human factor. How to communicate between operators, how to design the screens. I cannot explain how much this experience has helped me to go through the design phase for Nanit. How to do design sprints with parents, how to design the screens. The army is an amazing human resource filter that allocates hundreds of thousands of teenagers to specific positions and trains them in a short time and gives them practical experience. They are doing an amazing job. There are mistakes of course, but they took me and others and decided this is what you are going to do. They gave me tools for things that in the future were of great benefit to me.

AMLG: How does working on missile defense UX or chip manufacturing compare to baby monitoring?

AG: Ha well I continue to serve as a major in reserve. But in life I decided that I wanted to make a shift to deal with more human problems. What is nice about semiconductors is that they are designed by humans not by nature. Babies were designed by nature, which is more complex. When you have a blueprint you know exactly what you’re looking for, what kind of patterns. Then you can reach a level of analysis, of process control that is much higher. But the challenges with babies you know is?—

AMLG: They’re more of a mystery.

AG: It’s a lot of mystery. But my philosophy is to build the scientific fundamentals, the building blocks, and on top of that you think about how to make it approachable for the consumer space and how to build a value proposition. You start with science not marketing statements. This is where you start.

AMLG: A world of more ambient data capture where you’re continually monitored. Which feeds into preventative medicine. Obviously there’s a lot of people that get nervous about that, though it’s the way the whole world is going, we’re going to more data and it’s going to serve us. But as you push that conversation forward, do you feel like there’s challenges in terms of getting people used to the idea?

AG: You need to do it in a responsible way. But we can live a much better life. We will have better parenting experiences, sleep better at night. Even know things about ourselves that we didn’t know before.

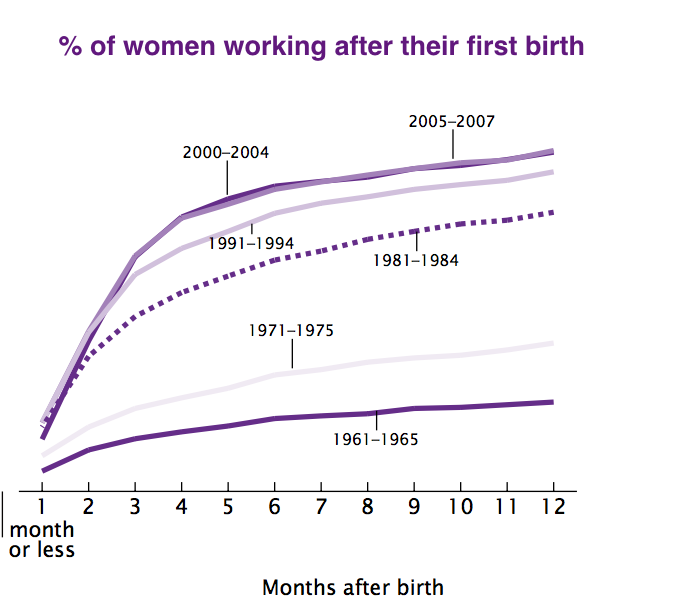

U.S Census Bureau Research 1961-2008

Further reading: