Knowing

what kind of reverb, and how much of it to add, are key aspects of producing a

professional sounding mix that combines sonic richness with energy and punch.

Reverb is, by definition, a means of adding space to sound, to give it context. It

identifies the sound as having been played somewhere; a medium sized room, a

cathedral, on a theatre stage or in a concert hall.

The actual components of a

rock track, for example, might have been recorded bone dry, but when it comes to

mixdown, it’s often the case that you’re looking to make the drum kit sound as

if it could have been played in a certain type of location; or maybe the idea

might be to create the impression that the whole band were just jamming along

in a medium sized ‘natural sounding’ studio room together.

The idea here is to

reconnect sounds that were recorded separately without any sense of space, and

give them some acoustic characteristics that can help them fit together as a

whole. On the other hand—if natural sounding is not your thing—reverb can easily

make anything sound distant, ethereal, otherworldly and even abstract in the

extreme.

Choosing which reverb to use in which context is a highly personal and

subjective decision, but understanding the various options will make the job a

lot easier.

Choose Your Space!

What types of reverb are there, and how can we know which type is most

suitable? It helps if you know how to pick a likely preset and then do a little

tweaking to make it ‘fit’ the specific situation you’re facing. Let’s take a

look at the main categories and also listen to the differences.

I’ve picked a

short clip taken from a track that features programmed drums, bass and electric

piano, with some live tenor sax playing as the lead instrument, and stripped it

back to just those instruments. The idea here is to try to add the different

types of reverb to the types of instrument where they might most often be

found, and see what difference they make to the overall sound.

First, let’s

hear the clip dry; everything has been set up with eq and compression, but just

no reverb yet. The drums were programmed with Toontrack Superior Drummer, so

you might hear some natural room mike sound already present on all the kit, but otherwise no extra reverb.

Cool Sax Scene Clip: Dry With Sax

Let’s take out the sax just for now,

so we can hear what’s going on a bit better:

Cool Sax Scene Clip: Dry No Sax

Plates

These

can be any size, but typically are quite dense and are full of early

reflections. A plate is not a naturally occurring space, but the name is

historical and derived from an acoustic phenomenon. The density of this type of

reverb, and the ‘carry’ it can have (if a longer decay time is chosen) means

that this is often used on snare drums, toms, and lead vocals as well.

Let’s

now listen to the clip with some plate reverb added to the snare; also the tom fill:

Cool Sax Scene Clip: Plate No Sax

Ambient Spaces/Rooms

This

is a small space or room that is big enough to give a little ‘life’ to a sound.

Think names like ‘tiled room’, ‘small studio’ (although some rooms can be quite

big). It isn’t big and lush sounding but can make a dry voice sound alive, or a

percussion instrument sound like it has space around it. Great for overheads,

hi-hats, bass drums, percussion, vocal speech and sometimes even guitars,

because you can make these things sound alive without losing too much of the

immediacy and impact of the dry sound.

How might adding a room reverb help our

clip? The electric piano was recorded dry, so let’s add some room to it and

include a touch of chorus within the reverb as well:

Cool Sax Scene Clip: Room No Sax

Chambers

Can

be a big, rich sounding effect. A

chamber is characterized by very few early reflections, so it generally sounds

smooth without any perceptible echo or slap back.

Let’s take our clip and add

the sax back in. I’m not convinced that a chamber reverb is quite right for the

sax, but let’s try it:

Cool Sax Scene Clip: Chamber With Sax

What

did you think? It makes the sax sound a bit distant and dense-sounding to me;

the reverb length is also too long at well over two seconds, so the overall

impression seems to sound a bit messy with reverb swilling about in the gaps.

Halls

These have a reflective pattern

similar to many natural performance venues. There’s usually a shortish

pre-delay, then early reflections begin followed by a more diffuse reverb

decay. They can be big (even massive), but the variations are endless and it’s

quite possible to set up quite intimate sized hall reverbs. Think names like

‘Small hall’, ‘Bright Theatre’ ‘Concert hall’ – or even ‘Madison Square

Gardens’ or ‘Taj Mahal’! (These are actual Lexicon MPX1 patch names.)

Let’s get back to our audio clip. Maybe a

smallish hall sound might work better on the sax? A little timed delay would be

pretty useful as well, also put back through the same hall reverb. In this case

I chose ‘Venue Clear’ from my TC Electronics M3000, and set it at slightly

under two seconds:

Cool Sax Scene Clip: Hall + Delay With Sax

Note: If you’d like to hear how the actual mix of the complete track ‘Cool Sax Scene’ turned out, it’s here on my AudioJungle page.

Convolution Reverbs

While we are on the subject of real

concert halls, we can now pick a patch that mirrors the exact sound

characteristics of real concert venues around the world, even to the last

degree of detail and complexity. Some plug-ins like Altiverb, Waves IR-1, and Logic’s

Space Designer exist to supply ‘real’ venue presets like this; you can then adjust

aspects of it according to taste. See Toby Pitman’s excellent article on

convolution reverb effects for more detail.

Reverb Parameters

Now that you’ve chosen your reverb

patch, what might need adjusting to fit the reverb into your track. There are

so many adjustable parameters it can seem like a daunting task! But if you’ve chosen

a good pre-set as a starting place, chances are only a few changes will be

needed from here. Here’s the main ones you should know about:

Reverb Decay

This

is the main thing really. Shortening or lengthening the reverb length is the

most common type of adjustment – maybe it’s all you need to do? Most

manufacturers know this and have made it easy to find. On 112dB’s ‘RedLine

Reverb’ it’s the big knob in the middle – you can’t miss it!

Pre-Delay

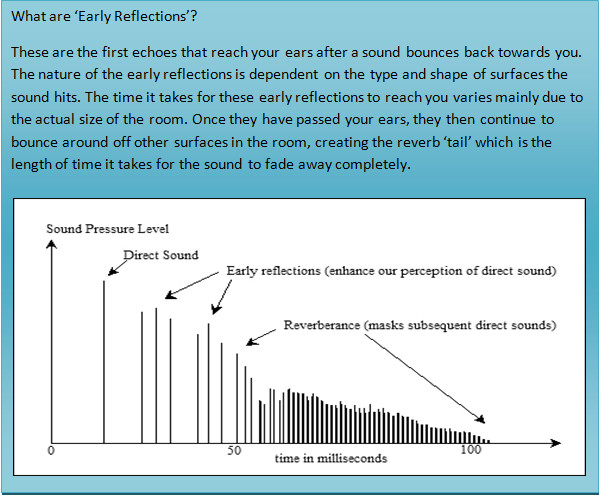

This

delays the start of the reverb (the early reflections – see below box) relative

to the dry sound. With a very short pre-delay, the sound ‘drowns’ in its own

reverb straight away, but with a long pre-delay, you have a chance to hear the

dry sound clearly before the reverb arrives. Nice on lead vocals – I always

think of adjusting this for that. Sometimes it can work nicely if the pre-delay

has a mathematical relationship to the actual tempo of the song.

Damping/EQ

High

frequencies tend to get absorbed quicker in a real reverberant space, so it is quite

natural to see a bit of an EQ ‘roll-off’ at the top end. Generally speaking, very

prominent frequency extremes are generally not especially useful – high

frequencies interfere with the clarity and too much low end can quickly make

drums or guitars seem muddy.

Diffusion

Technically it’s the rate at which

the echoes spread out after hitting the reflecting surface. A flat back wall

will send the sound back in one direction without much spreading out, but a

multifaceted surface will send the sound in all directions—add some furniture

in the room and the sound will diffuse even more. Not generally an adjustment I

spend too much time with, if I like the overall sound of the reverb anyway.

Modulation

Now this can be a bit of a

game-changer! I used to think this is why the old Lexicon 480L hardware could

sound so rich and textured compared with other much cheaper hardware units.

Something to do with the gentle chorusing, just on the tail of the reverb as it

dies away. (Or was it really just David Griesinger’s closely guarded reverb

algorithms?) It works really well on some things as a very gentle chorus effect

where you don’t actually want to add chorus to the dry sound. On the other hand… sometime pure reverb is the thing.

Wet/Dry Mix

Simply

put, this is how much reverb there is relative to the dry sound. Reverbs are

often added using an aux send, rather than inserted like a compressor.

Traditionally, this is simply because you might want to send several related

sounds to the same reverb in varying degrees – if you use a hardware mixer this

is very easy to do and modern day software equivalents are based on that

concept.

Summing Up

Reverb

is just a hugely important mixing tool. It gives a spatial context to

everything and is a huge help in bringing all your separate overdubbed track

sounds together and helping them to ‘gel’.

The danger is that it also tends to send

the sound towards the back of the mix. To use the whole soundstage, some things

have to be drier and more upfront.

This is why adding reverb to any track is a

hugely subjective thing. It’s all a matter of taste really—mix engineers have

used both reverb and compression in very different ways over the last 20 years

or so.

Delay Effects

Delays

are often used as an alternative effect to reverb, to create a sense of space

or maybe to enhance the groove in some way. They can be very easy to set up—just choose your speed and how much feedback (how many echoes or how much decay

you want to hear before the sound dies away) you need. Repeat echoes are often

closely related to the tempo or speed of the song.

Some people use charts to

calculate delay lengths, but a trick I still use is to divide 60,000 by the

tempo of the song to arrive at a figure that shows the length of a quarter or

half note in milliseconds for that song. You can then play with this number, by

dividing it again by two or some other number, to try out a tempo related delay

speed that might work well. Delay plug-ins often have a tempo ‘sync’ button—which gives me less of a headache working with the maths!

Delays can, of course, be mono or

stereo; they can gradually pan from side to side, or ping-pong from left to

right and back again. Most delay plug-ins like the Waves Supertap, have lots of

other parameters you can also adjust as part of the effect.

Here’s an image of

it; note there’s a visual display which encourages you to move the dry and

delayed signal around in space, either forward or backward or from side to

side:

Hardware-wise,

the TC Electronics D2 unit has options for adding chorus/modulation, reverse;

also dynamic level among other things. This is where the delay gets muted or

attenuated whenever the level of the signal gets too high—the delay then rises

at the ends of lines just as they begin to fade, which is useful on lead vocals

sometimes.

It’s great if you can automate the ‘ducking’ of a delay when its

presence isn’t needed, but I do find that some delays just need to be recorded

and edited to really work exactly as you want them to.

Here’s

an example of a particular type of stereo delay I have used a few times, where

there is a 4:3 relationship between the left and right sides, so one side is a

triplet subdivision of the song tempo and the other a division of four.

Another

well-used effect is to combine delay with reverb, by sending the delayed sound

through a reverb effect that gives a sense of it disappearing into the

distance. Modern day digital delays can sometime sound a bit clinical, so

another useful ploy is to roll off the EQ high end by degrees, thus simulating

what used to happen back in the days of recording with analogue tape machines.

These type of effects are often labelled up as ‘tape echo’ presets.

My Own Studio Set-up

You’ve probably guessed I still use a

lot of hardware reverb units when mixing! Sure there’s some awesome plug-ins

out there, but I still have several hardware units from an old studio set-up

and am keen not to tax my computer CPU power any more than absolutely

necessary.

I loved working with the Lexicon PCM90s and 91s back in the day,

but think that TC Electronic’s M3000 sounds just as good and is easier to use

in a hurry—I once did a thorough comparison test. I also have a couple of

Lexicon’s – an MPX1 and a MPX500. For the smaller ambient and room spaces I

often use the TC Electronics M1XL.

{excerpt}

Read More