I’m a procrastinator. I’m also easily distracted, both in the short term (incessantly checking my Twitter account) and also over longer periods. I’ll become consumed with an idea for a new project before the current one is finished. It’s frustrating for me and those around me.

You’re probably similar. Most of us have trouble maintaining focus, and it’s getting more difficult all the time. For me, connectivity is the problem.

We live in an age of ubiquitous information and communication, so distractions have never been more pervasive. We have too many choices of what to look at or focus attention on. The internet is a glittering carnival of diversions, and that’s wonderful – until you need to get some work done.

The enemy here isn’t the net, of course; it’s you. You’re the one being distracted. Willpower can be a dwindling resource, and the problem is compounded by background noise, low blood-sugar, or a poor night’s sleep. Sometimes it’s all we can do to just check our email and maybe read the news.

We are capable of productivity, though. I suffer from periodic insomnia, and even in the late afternoon of the second full day with hardly any sleep, I can produce valuable creative output. It’s by no means the ideal situation, but it’s possible. It’s also uncommon. Most of the time, unless I’m energised and fed and “in the zone”, focus is a struggle.

The mains power supply to our home hadn’t been upgraded in decades, and the power company recently decided to make some improvements. We were given several weeks’ notice of the day when we’d have no power. It turned out to be a warm, sunny Wednesday in early July, and the electricity supply was cut off between 08:30 and 17:00. I had to actually be present the whole day because part of the work was inside at our switchboard, so I was faced with a day of dubious productivity without the internet.

Instead, it was a day of enormous productivity. Whilst I of course still had my phone and could readily have tethered a laptop to it, I chose not to. I did check email and twitter on the phone, but the simple act of it being on a separate (and small) device relegated those tasks to the background, in a way they hadn’t been for years.

It got me thinking. The internet is still relatively new, and we all certainly remember when getting online was at least arduous, if no longer quite impossible. Dial-up bandwidth, a single phone line, and machines that sometimes struggled with being dragged into the internet age. I owned many such machines, and decided to reacquire a few, just to see how they felt. I wanted the focus, knowing full well that it was because of what those devices were incapable of (or at least what was difficult for them).

When I was a teenager, I wrote on an Amstrad Notepad Computer NC100, so I got another one.

It can print via a parallel cable, save files to ancient PC Cards, or in its most impressive feat, transmit files via xmodem over a serial cable. That’s it. The battery life (in the 4xAA sense) rivals all but this year’s MacBook Airs. You can really write on this thing, because it can barely do anything else.

Next on the list was a beautiful old PowerBook; I chose a 150, with its monstrous wrist-mangling keyboard, smeary 4-grey passive matrix display, and an internal hard drive that sounds like an office photocopier’s death rattle. It’s a gorgeous old beast, and it has Word 5 on it (5.0 rather than 5.1, sadly, but it has far more modest requirements).

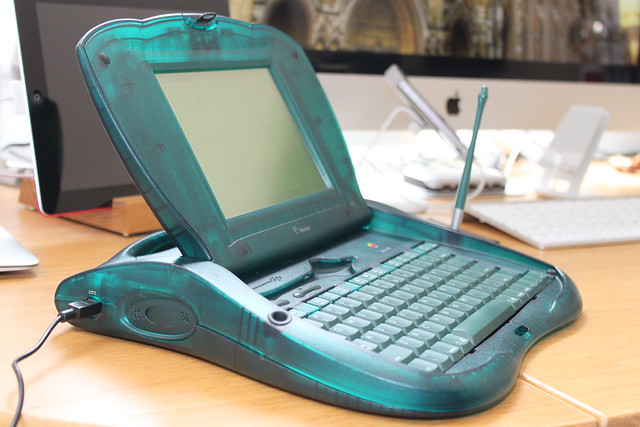

Then there’s my instantly-beloved eMate, the one and only Newton device with a laptop-like form factor. It’s sort of like a pen-tablet with a keyboard case, and its industrial design is what I imagine the Borg would have used if they’d been introduced during the original Star Trek series rather than Next Generation.

The eMate can get online, but it’s only barely up to the task: web page loading and rendering times make you remember why we had progressive JPEGs. Like its Newton MessagePad cousins, its connectivity is for routing (in Newton OS parlance) rather than browsing or socialising. You make a connection in order to send or receive something, then you go offline again. Just like when you had to get the fax-modem out of your bag to do so.

There’s no question that each of these devices would have been equipped with wi-fi and 3G had those technologies been around at the right time. There was no judicious omission; no worship of focus. But we can use them that way now, even though it’s a happy accident.

There’s a lot to be said for frictional connectivity. By all means get online – we do need to, from time to time – but realise the benefit in making it at least a little difficult for yourself. Keep the distractions at arm’s length.

Patrick Rhone recently wrote on a similar topic, which lead me to this wonderful selection of writing sheds. You can see George Bernard Shaw’s, and Roald Dahl’s, and of course Dylan Thomas’ boathouse. They weren’t indulgences. They were places of focus, for people whose creative output depended on it. They were acknowledgements that even a ringing phone, or footsteps from an upstairs room, can be enough to derail concentration for many of us. With all the attractions of the internet, a creaky floorboard is the very least of our concerns.

We act as if we take concentration for granted, yet everyone has had trouble keeping their mind on the task at hand. We litter our menubars with icons, keep notifications enabled, and run our email programs, chat apps and social media clients all day. Something’s got to give, and invariably it’s our creative output.

I had a piece to write for a magazine recently, and decided to see how I’d get on if I cut out all the distractions. I left my phone in my office, and took the eMate through to the sofa (and, I admit, a glass of whisky). My wife was away on a business trip, so all I could see was the slightly eerie green glow of the eMate’s screen showing a blank page in Newton Works, and all I could hear was the whine of the backlight’s old transformer. The words flowed, and I was done in an hour. I’ve since repeated the experiment, with the same result. And the whisky was a control variable.

I’m not suggesting you scavenge eBay for a vintage proto-laptop, of course. Instead, I think we can bring our current technology back just far enough in time to let us breathe and think. The first thing I tried was creating a Parental Controls-limited account on the MacBook Air. It’s great for its stated purpose of keeping your kids from destroying either the machine or their young minds, but it’s useless for focus. Limiting your choice of apps isn’t what’s needed, and the temptation always remains: full functionality is just an admin password away. I need quite a bit more force to keep me honest.

Enter two gems: Freedom ($10) and Anti-Social ($15). Both are for Mac OS X, and you can buy both together for $20, which is what I did. They’re essentially the same utility, except that Anti-Social blocks a specific list of sites (defaulting to social media sites, but you can add your own too), whereas Freedom kills your internet connection entirely.

You get to choose how long it’ll be active (between 15 minutes and 8 hours), and that’s it. There’s no cheating, either; no unlocking early. Once it’s on, your only options are to either wait it out, or reboot the machine. That’s exactly how much persuasion I need: to not be given the ability to be weak at all.

Personally, I tend to keep my writing in Dropbox for easy sync between machines, so disabling the whole net connection with Freedom is usually overkill. Instead, I plug a list of sites into Anti-Social, and leave basic connectivity active.

My suggested list of sites to block would be:

- Facebook, Twitter and App.Net. Google+ if you use it.

- Any social-related vanity sites, like Favstar or Topsy.

- Your news sources, including your feed-aggregation service (which has the nice side-effect of rendering feed reader apps useless too).

- Reddit, Hacker News, etc.

- Any comics or similar sites you read during breaks.

- Amazon and eBay. Maybe etsy too, or that other place you shop.

- Any forums you frequent.

- The authentication servers for any online games you play.

It remembers your list of blocked sites between invocations. The block is at the system level, so the sites will be unreachable regardless of whether you’re using a browser or a dedicated app – which is exactly what you want.

We have limited time. Our workdays are only so long. Our evenings. Our lives. We spend too much of that time on trivia. Some distraction is healthy and necessary, but we all know that the scales have long since tipped.

The internet isn’t to blame – it’s us. We’re weak, and our natural tendency is to feed that weakness rather than struggle against it. Some people are more prolific than others, but the boundaries don’t lie where we think they do: context and self-discipline are much, much more important than your personal pace or ability. The difference that a creativity-conducive environment can make is profound.

I personally don’t seem to be able to choose to ignore Twitter, or email, or BBC News when they’re available. I can manage for short periods, but sooner or later I’ll give in. What I can do, though, is remove the temptation. Counting the chocolate bars in the cupboard doesn’t work half as well as just not buying any. I know it, and so do you.

Most of us can’t realistically take our work out to a shed (presumably with a Faraday Cage installed, these days), but we can use technology to build that shed – a place of focus, filtering out distractions – around us, wherever we are.